The artistic renewal that developed between the late 19th and early 20th centuries, exactly between 1894 and 1914, marked a significant transformation in the art world, often referred to as fin de siècle or the belle époque.

The term Art Nouveau was first used around this time—coined in Belgium by the magazine L’Art Moderne to describe the works of the artist collective Les Vingt, and in Paris by Siegfried Bing, who named his gallery L’Art Nouveau. Depending on the country, the style took on different names depending on the country: Art Nouveau in Belgium and France, Jugendstil in Germany and the Nordic countries, Sezession in Austria, Modern Style in the United Kingdom, Nieuwe Kunst in the Netherlands, Liberty or Floreale in Italy, and Modernismo in Spain.

The 40 different names of Art Nouveau explains the many names that art nouveau, not just the eight commented above. Despite the varying names, all of these terms point to the same intention: to create a new, young, free, and modern art. As with many artistic movements, it sought to break away from the past with a clear message: “the future has already begun.”

There was a strong emphasis on craftsmanship, while still embracing industrial advancements. A key aspiration was to democratize beauty and socialize art, promoting the idea that even everyday objects should have aesthetic value and be accessible to the general public. As a result, functional objects of daily life became aesthetically significant, including urban furniture, such as kiosks, subway stations, streetlights, trash bins, and public restrooms.

This movement erased the hierarchy between “high” and “low” arts. A building was considered just as valuable as a piece of jewelry, and a poster as important as a painting. In fact, artists often created the frames for their paintings, and architects designed the furniture for their buildings.

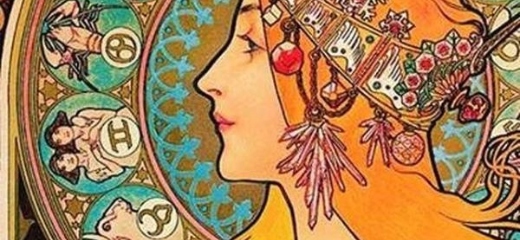

Aesthetically, there was a clear inspiration from nature: plants and organic forms intertwined with central motifs. Straight lines were abandoned in favor of curves and asymmetry, creating a more sensual style aimed at pleasing the senses.

In this artistic context, flowers, leaves, twisted stems, insects, and flowing feminine hair filled the entire visual space, embracing the concept of horror vacui—the fear of empty space.

Art Nouveau was an ornamental art style that thrived between 1890 and 1910 across Europe and the United States. It is best known for its use of long, flowing, organic lines and was widely applied in architecture, interior design, jewelry, glasswork, posters, and illustrations. The movement aimed to break away from the prevalent historicism of 19th-century art and design by introducing something entirely fresh and original.

In England, the roots of Art Nouveau can be traced to earlier movements like Aestheticism, exemplified by the work of illustrator Aubrey Beardsley, whose art focused on the expressive potential of organic lines. Another key influence was the Arts and Crafts movement, led by William Morris, who emphasized the importance of craftsmanship and integrating artistic style into everyday objects.

On the European mainland, Art Nouveau drew inspiration from the bold, expressive lines of painters like Paul Gauguin and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. Additionally, the movement was shaped by the growing fascination with the stylized, flowing patterns found in Japanese prints (ukiyo-e), which had a significant impact on the development of Art Nouveau’s signature linear style.

One of the defining features of Art Nouveau is its flowing, asymmetrical lines, often inspired by elements from nature such as flower stems, buds, vine tendrils, insect wings, and other organic, delicate forms. These lines can be either graceful and elegant or imbued with a dynamic, whiplike energy. In the graphic arts, the line takes precedence over all other visual elements—form, texture, space, and color—serving primarily as a decorative tool.

In architecture and other three-dimensional arts, this organic linearity envelops the entire form, creating a seamless fusion between structure and ornamentation. Architecture, in particular, demonstrates this merging of design and decoration. Artists and architects utilized a diverse range of materials—such as iron, glass, ceramics, and brick—to create cohesive, unified interiors. Columns and beams were transformed into thick vines with spreading tendrils, while windows became both functional openings for light and air, and extensions of the organic forms that characterized the style.

This approach stood in stark contrast to traditional architectural principles, which emphasized clarity, structure, and rationality. Art Nouveau instead embraced a more fluid, ornamental vision, where structure and decoration were inseparable.

A large number of artists and designers contributed to the Art Nouveau movement, each bringing their own unique style to the decorative arts. Among the most notable figures was Scottish architect and designer Charles Rennie Mackintosh, who favored a predominantly geometric aesthetic and had a significant influence on the Austrian *Sezessionstil*. In Belgium, architects Henry van de Velde and Victor Horta became known for their extremely fluid and delicate structures, which, in turn, influenced French architect Hector Guimard, another key figure in the movement.

In the United States, glassmaker Louis Comfort Tiffany was renowned for his exquisite stained glass creations. France produced several important Art Nouveau artists, including furniture and ironwork designer Louis Majorelle, as well as René Lalique, celebrated for his intricate glass and jewelry designs. Czechoslovakian graphic designer and artist Alphonse Mucha also left a lasting mark with his iconic posters and illustrations.

Across the Atlantic, American architect Louis Henry Sullivan incorporated plant-like Art Nouveau ironwork into the ornamentation of his otherwise traditional buildings. Lastly, Spanish architect and sculptor Antonio Gaudí emerged as perhaps the most original artist of the movement, transcending the typical reliance on linearity to create buildings that were curving, bulbous, brightly colored, and deeply organic in their form.

After 1910, Art Nouveau began to be seen as old-fashioned and limited, leading to its abandonment as a distinct decorative style. However, in the 1960s, the movement experienced a revival, partly due to several major exhibitions that helped rehabilitate its reputation. These included exhibits at the Museum of Modern Art in New York (1959), the Musée National d’Art Moderne in Paris (1960), and a large-scale retrospective on Aubrey Beardsley at the Victoria & Albert Museum in London in 1966. These events elevated Art Nouveau from being regarded by some critics as a fleeting trend to being recognized alongside other major Modern art movements of the late 19th century.

Elements of the movement were revitalized in Pop and Op art, while in popular culture, the flowing, organic lines of Art Nouveau found new life in the emerging psychedelic style. This influence was evident in fashion, typography, and the design of rock and pop album covers, as well as in commercial advertising.

In our website https://artnouveau.club you can discover itineraries in the main European art nouveau cities.

8 movements inspired and influenced Art Nouveau, the “new art style” that embraced Europe’s new industrial aesthetic . It featured naturalistic but stylised forms, often combined with shapes which were more geometric like parabolas, and semicircles. The movement used forms from the natural world that had not been used for long like insects, weeds, even mythical faeries.

Only a few can distinguish what inspired and influenced this and what didn’t. Curved lines were preferred to straight parallel lines, but there is more to consider. Check if you are one of them. Test your skills by clicking this link.

Art Nouveau spread, almost at the same time from 1880 to 1914. This style was spread pretty fast throughout Europe thanks to photo-illustrated art magazines and international exhibitions and reached North and South America as well. A proof of the importance presence of Art Nouveau in America is the first Ranking of American Art Nouveau cities according to their Art Nouveau heritage and attractive, elaborated with the help of its large number of social network followers (that used surveys with the participation of more than a thousand of them), clients and Academic experts from museums and representatives from several Arts Institutions. The top 3 cities are Buenos Aires, Havana and Lima.

Characterized by sinuous lines and the distinctive “whiplash” curves, Art Nouveau found its roots in botanical studies and illustrations of marine life, notably exemplified by German biologist Ernst Heinrich Haeckel (1834–1919) in his seminal work “Kunstformen der Natur” (Art Forms in Nature, 1899). Influential publications like “Floriated Ornament” (1849) by Gothic Revivalist Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin (1812–1852) and “The Grammar of Ornament” (1856) by British architect and theorist Owen Jones (1809–1874) advocated for nature as the primary wellspring of inspiration, challenging a generation of artists to break free from conventional styles.

The flowing lines of Art Nouveau can be seen as a metaphor for the sought-after freedom and liberation from the weight of artistic tradition and critical expectations. The movement’s embrace of organic forms reflected a desire for a departure from established norms, symbolizing a profound shift in artistic expression during that transformative era.

Furthermore, the genesis of the new style found its roots in two significant English developments of the nineteenth century, both fueled by the impetus for design reform. This reform was a reaction to prevailing art education, the rise of industrialized mass production, and the dilution of historic styles. The Arts and Crafts movement and the Aesthetic movement were pivotal in shaping this transformative era.

The Arts and Crafts movement advocated a return to handcraftsmanship and traditional techniques as a response to the mechanization of mass production. Simultaneously, the Aesthetic movement championed the credo of “art for art’s sake,” laying the groundwork for non-narrative paintings like Whistler’s Nocturnes. This movement also drew inspiration from Japanese art, known as “japonisme,” which surged into Western markets, primarily in the form of prints, following the establishment of trading rights with Japan in the 1860s. Indeed, the spectrum of late nineteenth-century artistic trends, encompassing painting and the early designs of the Wiener Werkstätte, can be loosely categorized under the umbrella of Art Nouveau.

The term “art nouveau” made its debut in the 1880s through the Belgian journal L’Art Moderne, describing the work of Les Vingt—a collective of twenty painters and sculptors dedicated to reform through art. Reflecting the broader artistic community across Europe and America, Les Vingt responded to the influential nineteenth-century theorists such as French Gothic Revival architect Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc (1814–1879) and British art critic John Ruskin (1819–1900). These theorists advocated for the unity of all arts, challenging the segregation between the fine arts of painting and sculpture and the so-called lesser decorative arts.

Deeply influenced by the socially conscious teachings of William Morris and the Arts and Crafts movement, Art Nouveau designers aspired to achieve the synthesis of art and craft. Moreover, they sought the creation of the spiritually uplifting Gesamtkunstwerk, or “total work of art,” spanning various media. This successful integration of the fine and applied arts materialized in complete designed environments such as Victor Horta and Henry van de Velde’s Hôtel Tassel and Hôtel Van Eetvelde (Brussels, 1893–95), Charles Rennie Mackintosh and Margaret Macdonald’s design of the Hill House (Helensburgh, near Glasgow, 1902–4), and Josef Hoffmann and Gustav Klimt’s Palais Stoclet dining room (Brussels, 1905–11).

Styles such as Post-Impressionism and Symbolism (the “Nabis”) shared close ties with Art Nouveau, influencing applied arts, architecture, interior designs, furnishings, and patterns, contributing to an overall expressive and cohesive style.

In December 1895, the German-born Paris art dealer Siegfried Bing opened L’Art Nouveau gallery, credited with popularizing the movement. The Art Nouveau style reached an international audience through vibrant graphic arts in periodicals like The Savoy, La Plume, Die Jugend, Dekorative Kunst, The Yellow Book, and The Studio. Influential graphic artists included Aubrey Beardsley, Alphonse Mucha, Jules Chéret, and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec.

Art Nouveau style, associated with France, received various names, including Style Jules Verne, Le Style Métro, Art belle époque, and Art fin de siècle. The movement captivated the public at the 1900 Exposition Universelle in Paris, showcasing innovative structures like the Porte Monumentale and the Pavilion Bleu.

The movement was also prominent in other style centers across Europe, known by different names such as Jugendstil in Germany, Modernista in Barcelona (with Antoni Gaudí as a key figure), Arte nuova and Stile Liberty in Italy, Sezessionstil in Austria and Hungary, and Stil’ modern in Russia. In the United States, it was referred to as “Tiffany Style” due to the influence of Louis Comfort Tiffany.

While Art Nouveau was a short-lived movement, its influence persisted, shaping subsequent design movements like Art Deco. The dramatic graphics of Art Nouveau found a resurgence in the 1960s, reflecting a new generation challenging conventional taste and ideas.