The Sprudelhof in Bad Nauheim, as the largest fully-preserved Jugendstil ensemble in Europe, is a remarkable monument to German Art Nouveau. It embodies the movement’s core tenets: its deep connection to nature, its versatile aesthetic ranging from floral to geometric, its ambitious ideal of the Gesamtkunstwerk, and its innovative use of materials. The complex stands as a powerful testament to an era when artists and architects sought to redefine the role of art in society, creating an “aesthetic of modernity” that was both beautiful and purposeful. Its preservation is a vital part of Europe’s cultural heritage, reminding us of a time when beauty and healing went hand in hand.

The Dual Essence of German Jugendstil: From Nature to Geometry

The Art Nouveau movement, known in Germany as Jugendstil or the “style of youth,” was a transformative artistic force that emerged in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It represented a powerful and deliberate reaction against the prevalent academicism, eclecticism, and historicism of the 19th century, advocating for a “new art” that was both modern and unburdened by the conventions of the past. While specific sources might not detail the Sprudelhof in Bad Nauheim, an understanding of Jugendstil’s core principles and aesthetics allows us to appreciate how a landmark spa complex in Germany during this period would have embodied the style. The Sprudelhof, the largest self-contained Art Nouveau ensemble in Europe, stands as a stunning testament to the synthesis of modernity, nature, and wellness that defined German architecture of the era.

At its heart, Jugendstil drew profound inspiration from the natural world, translating organic forms into a decorative vocabulary defined by sinuous, rhythmic, and curvilinear lines often described as “whiplash lines.” Botanical and zoological motifs—from flowers and tendrils to insects and mythical creatures—were ubiquitous in its compositions, celebrating nature’s unbridled beauty. This initial “floral Jugendstil” phase, epitomized by artists like Otto Eckmann, sought to immortalize the graceful, fluid lines of the natural world in every aspect of design.

However, German Jugendstil was not a singular, static style. Towards the late 19th and early 20th centuries, a significant shift occurred. Centers like Darmstadt and artists such as Peter Behrens began to evolve toward a more severe, geometric aesthetic. This new phase was characterized by abstract, simplified forms, straight lines, right angles, and symmetrical structures, with a heightened focus on the interplay of light and shadow. This versatility and duality between the ornate and the rectilinear allowed Jugendstil to adapt to a vast range of applications, from intricate decorative arts to monumental architectural projects.

The Quest for a “Total Work of Art” (Gesamtkunstwerk)

A central and deeply philosophical ideal of Art Nouveau, and thus Jugendstil, was the concept of the Gesamtkunstwerk, or the “total work of art.” This aspiration went far beyond mere building design; it was a holistic vision that sought the harmonious and cohesive integration of all artistic elements within a space. This meant that everything—from the building’s architecture and exterior details to its interior furnishings, lighting, textiles, and decorative objects—was conceived as a unified whole.

This holistic approach was driven by a sense of “great moral responsibility” felt by designers of the time. They believed that by creating objects of fine craftsmanship, they could counter the low quality of mass-produced goods. This philosophy found a perfect canvas in public buildings like spas, where every detail could contribute to a cohesive, immersive experience that was not only beautiful but also enriching and purposeful. It was an ambitious attempt to unify all aspects of life under a single artistic vision, blurring the lines between art, craft, and everyday existence.

Innovation in Materials and Architectural Surfaces

Jugendstil architecture was a laboratory for innovation in the use of materials and construction techniques. Architects moved away from the common practice of painting over surfaces, instead valuing the natural visual qualities of materials like plaster, brick, and ceramic tiles. They experimented with different textures and finishes, creating a new level of detail on facades. The period saw the development of special plaster patterns and prefabricated Roman cement elements, allowing for intricate decorative accents. The focus was on “constructive truth”—letting the materials speak for themselves. This attention to surface and texture was key to the style’s aesthetic, which often featured unpainted, fine-textured plaster. This approach provided a perfect backdrop for the graceful ornamentation of the style, demonstrating a modern sensibility that was both functional and visually rich.

The Sprudelhof: An Architectural Embodiment of an Ideal

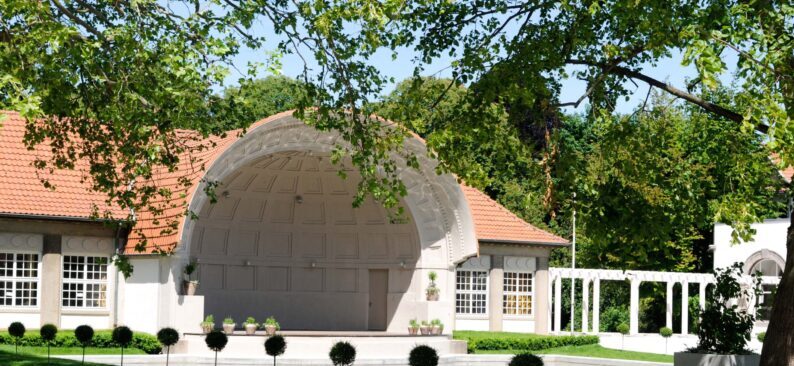

The Sprudelhof, as a spa complex, stands as a magnificent, real-world application of all these Jugendstil principles. Its very purpose—healing through natural waters—perfectly aligned with the movement’s reverence for nature. This connection would have been expressed not just in its architectural forms but in every detail, from the decorative motifs of the facades to the patterns of the mosaics and the design of its fountains, all of which would evoke the purity and regenerative power of the healing waters.

The complex was built during the Belle Époque, a period of unprecedented economic, technical, and social progress. A public building of this scale would have been a symbol of urban refinement and modernity. Jugendstil, with its emphasis on the “new” and its rejection of historicism, was the ideal style to convey this avant-garde image of health and urban sophistication. The Sprudelhof would not only have provided a functional space for wellness but would have transformed the experience into an art form itself.

The Gesamtkunstwerk ideal would have found its ultimate expression here. Every element, from the bathhouses and hotels to the interior furniture, signage, and lighting, would have been meticulously crafted as a unified whole, creating an immersive, multi-sensory experience. This holistic approach prioritized not only aesthetics but also “practical viewpoints” and “functional” solutions for interior spaces. The result was a space where art and wellness were inseparably linked, a place where a visit was not just a medical treatment but a complete aesthetic and spiritual retreat.

Complete information about this historic site just 45 km north of Frankfurt, in their Tourist Information website.