Art Nouveau was a popular style that emerged in the late 19th century and lasted until the early 20th century. It was characterized by its use of organic and flowing forms, as well as its emphasis on craftsmanship. However, the style eventually fell out of favor and was replaced by other movements. There are several reasons why Art Nouveau was short-lived.

One reason is that it was expensive to produce. The intricate designs and handcrafted details required a high level of skill and artistry, which made the cost of production high. This made it difficult for the style to be widely adopted, as it was only accessible to a small segment of the population.

Another reason is that it was difficult to mass-produce. The organic and flowing forms of Art Nouveau were not well-suited to mass production techniques. This made it difficult to create large quantities of Art Nouveau products, which further limited its appeal.

Additionally, Art Nouveau was seen as being too decorative and impractical. The style was often criticized for being more concerned with aesthetics than with functionality. This led to the perception that Art Nouveau was not a serious or practical style, which contributed to its decline.

Finally, Art Nouveau was a victim of changing tastes. As the 20th century progressed, people’s tastes began to change. They became more interested in simpler and more functional designs. This led to the rise of new styles, such as Art Deco and Bauhaus, which eventually eclipsed Art Nouveau.

Despite its short lifespan, Art Nouveau had a significant impact on the world of art and design. It helped to pave the way for modernism and other subsequent movements. Today, Art Nouveau is still appreciated for its beauty and craftsmanship.

Timeline of art nouveau style movement

From the 1880s until the First World War, a wave of artistic revolution swept across Western Europe and the United States. This movement—Art Nouveau, or “New Art”—emerged as a rebellion against tradition, drawing inspiration from the untamed elegance of nature. Sinuous lines, twisting tendrils, and flowing curves defined its essence, mirroring the organic rhythm of the world itself.

Artists found a muse in the unseen wonders of deep-sea life and botanical studies, their forms immortalized in Ernst Haeckel’s mesmerizing illustrations. The movement also echoed the philosophies of visionaries like Owen Jones and Augustus Pugin, who urged creators to abandon the rigid echoes of the past and instead turn to nature as the ultimate guide. To Art Nouveau’s devotees, its sweeping curves were more than just an aesthetic choice—they were a metaphor for liberation from the weight of artistic convention.

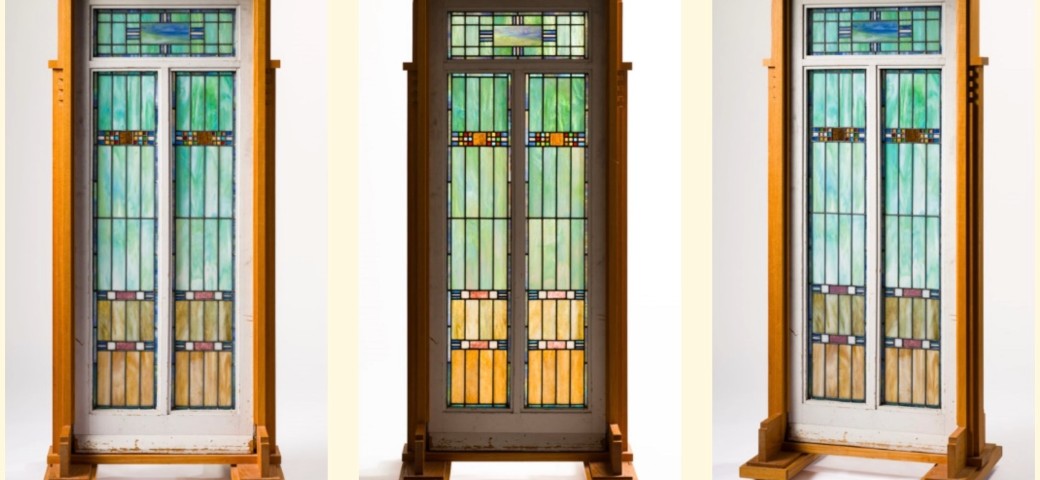

But Art Nouveau did not emerge from a vacuum. It was born from the embers of two English movements that had already begun to challenge the status quo. The Arts and Crafts movement, with its passionate call for handcraftsmanship over soulless industrial production, provided a foundation of integrity. Meanwhile, the Aesthetic movement’s cry of “art for art’s sake” fueled a pursuit of beauty untethered from narrative or tradition. Japanese prints flooded Western markets, igniting a fascination with asymmetry and stylized forms. Together, these influences wove the tapestry from which Art Nouveau would rise.

As its influence spread, the movement took on different names in different lands. In Belgium, it was Style coup de fouet—”whiplash style”—named for its dramatic, curling lines. In Germany, it became Jugendstil, or “young style,” after the avant-garde magazine Die Jugend. In Italy, it flourished as Stile Liberty, a nod to the famed London department store that introduced English audiences to this radical aesthetic. Even the United States saw its own interpretation, as Louis Comfort Tiffany transformed glass into shimmering poetry.

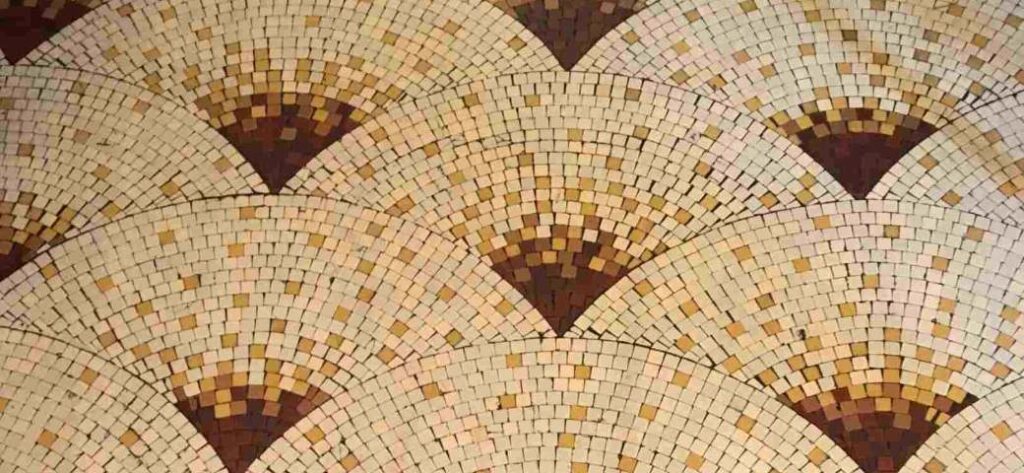

Yet it was in France that Art Nouveau truly made its grand entrance. The 1900 Exposition Universelle in Paris was its moment of triumph, a dazzling spectacle of craftsmanship and imagination. The city’s streets were adorned with Hector Guimard’s iron-and-glass metro entrances, their tendrils unfurling like vines in an urban jungle. Furniture by Georges de Feure and Louis Majorelle fused Rococo fantasy with Art Nouveau’s organic grace. The bold, sensual illustrations of Alphonse Mucha and Aubrey Beardsley graced posters, magazines, and books, captivating a generation.

This movement, however, was destined to burn bright and fade quickly. The arrival of modernism ushered in a new philosophy—one that valued function over flourish, geometry over fluidity. Art Nouveau’s dreamlike, ornamental world gave way to the sleek lines and bold structures of Art Deco. While both movements shared a love for innovation and craftsmanship, their souls were vastly different. Art Nouveau danced with nature’s wild beauty, its forms echoing vines, waves, and blossoms. Art Deco, in contrast, was a celebration of speed, industry, and modernity—sharp, symmetrical, and unapologetically bold.

Though fleeting, Art Nouveau left an indelible mark, shaping everything from architecture to graphic design. Even today, its legacy lingers in the curling ironwork of balconies, the elegant typography of vintage posters, and the dreamlike jewelry of Lalique. It was a movement that sought to transform the world into a total work of art—one where beauty was not a luxury, but a way of life.

Where Art Nouveau celebrates elegant curves and long lines, Art Deco consists of sharp angles and geometrical shapes. Although often confused, the two movements mark entirely different directions in the development of modern art. Check the differences and test if you know the differences well HERE.