The American dancer Marie Louise Fuller (1862-1928) was born in a tavern in a suburb of Chicago, in the United States, where her parents had taken refuge from the winter cold. When she came of age she still lived in poverty: the money she earned from her theatrical performances barely gave her a single daily ration of food.

Little did she know that she would end up becoming an internationally famous ballerina, applauded by the Tsar of Russia or the Kaiser of Germany.

About her life

She achieved international distinction for her innovations in theatrical lighting, as well as for her invention of the “Serpentine Dance”, a striking variation on the popular “skirt dances” of the day.

Her first steps towards success were taken in her early thirties, thanks to a dance number that she included in circus and variety shows. In it, she wore a long skirt that she moved imitating a flutter while she pretended to be hypnotized.

That “serpentine dance” would cause a furor in Europe, where she settled in 1892, and made her the muse of art nouveu and propelled her to world fame: among Fuller’s long list of friends were the symbolist poets Paul Valèry and Mallarmé, the sculptor Rodin, Toulouse-Lautrec, the Viennese modernist Koloman Moser and a long etcetera.

When she moved to Paris in 1892, she instantly found success and community within the city’s art world, gaining her the French nickname Loïe Fuller. Paris at that time was a hub of artistic freedom just as the Art Nouveau movement blossomed in the city, and Loïe the American free-movement dancer was at the best place to succeed.

She impressed at the Parisian Folies Bergère for the way she undulated the hundreds of meters of silk in her dress and for the transparency of it, without a corset covering her body. Loïe also patented a series of chemical compounds to produce special color effects on her clothing, and she used luminescent salts for the first time to create stage lighting tricks.

Her style was unique

At her house, he experimented with chemical substances such as magnesium to achieve these plays of light and color. It is not surprising that among her friends were the scientists Pierre and Marie Curie, discoverers of radium. With them she shared seances, which was also attended by a common friend, the astronomer Camille Flammarion.

Her ghostly dance captivated poets, writers and painters such as Rodin and Toulouse-Lautrec. But it was never the wonderful sylph that artists immortalized in posters, photographs, sculptures, lamps and all kinds of objects in the modernist Art Nouveau style.

In reality, Fuller was a stocky woman with a vulgar face and upturned nose, who spoke broken English and bad French.

The artist also enthused Queen Maria of Romania, with whom she maintained a close friendship and extensive correspondence. Both staged more than one scandal in the press. She wasn’t the only woman she loved.

With Gabrielle Bloch, a dancer sixteen years her junior, she shared three decades of her life. In her biographie Quinze ans de ma vie (1908), Fuller had no qualms in stating: “For eight years we lived together in the greatest intimacy, like two true sisters.”

She openly lived her lesbian sexuality. She was confirmed by the American Isadora Duncan, whom she Fuller introduced to the European stages, during her brief stint at the dance school of her compatriot. It struck Duncan that so many of Fuller’s students were so warm to her mentor.

The brand new cinema recorded her dance. The brothers Auguste and Louis Lumière filmed it on stage. And she herself directed, produced and performed a short, Fire Dance, in which she danced while some lights were projected on her clothes, giving the impression that fire was licking her body.

The pioneer of modern dance

Despite lacking training in classical ballet and formal dance techniques, she paved the way for dancers such as Duncan herself, the American Martha Graham, and the Russian Michel Fokine. She was a celebrity and one of the highest paid entertainers of her time.

However, after her death from pneumonia at age 65, she fell into oblivion. Her innovative talent was recognized not long ago by American dancers and historians.

She quickly embodied the movement, using her costumes and gestures to mimic the art style characterized by flowing shapes and intricate patterns. Fuller experimented with chemical lighting and use of stage lights in her performances to alter the colors of her costumes, and she earned more than a dozen patents for it.

From her success in Paris, she bought an elegant mansion at 24 rue Cortambert in the city’s 16th Arrondissement where she and her partner—a woman named Gab Sorère—lived together until 1928, when Fuller died from pneumonia at age 65. Though visitors can’t go inside the residence and take a tour, Zimmer encourages individuals to think outside the box when visiting the homes of artists like Fuller.

“Put yourself in the shoes of great people for a second, like: They stepped through that door, that’s the view they saw when they walked out of their house,” Zimmer says. “It’s really special to see something mundane that a genius saw every day while they lived there.”

The muse of ‘art nouveau’ and of the French symbolist poets

Her movements were not canonical and responded to the spontaneous reaction of the body when it is carried away by music. The long skirt and the wide silk tunics with which she performed were also out of the norm: on the moving fabric she projected colors with light effects that she designed herself and the result left those who watched the show speechless.

All this was happening at the end of the 19th century, when there was no such thing as modern dance.

She wasn’t even slender and slim, but that didn’t matter when she began to dance. For her shows, she invented new lighting systems; she devised the costumes and finally eclipsed the stage waving her arms and managing her body producing energy in gushes. Her movements were based on the arrangement of the flower petals, on different insects and atmospheric phenomena.

She was a support for her compatriot the dancer Isadora Duncan (15 years younger) whom she welcomed as her protégé and helped her to enter Europe in 1902.

The avant-garde creator went beyond dance and that is why she inspired intellectuals and artists in so many different fields, she covered her choreographies with disciplines that had never been related to dance before.

From the sculpture of Auguste Rodin to the advances in the field of radium made in those years by Pierre and Marie Curie (also personal friends of the artist), her voracious curiosity allowed her to interpret the world as a container of valuable knowledge.

Loïe Fuller: Pioneer of Modern Lighting Technology

Loïe Fuller invented new lighting systems for her shows, she herself creating the scenic apparatus and directed teams of up to almost 40 technicians; she was a visionary artist who revolutionized the world of dance and theater in the early 20th century. She was known for her mesmerizing performances that combined dance, theater, and visual art, and her innovative use of flowing costumes and lighting effects. In particular, Fuller was a pioneer of modern lighting technology, working closely with inventors and engineers to develop new and innovative ways to light up her performances.

Fuller’s collaboration with Nikola Tesla, the famous electrical engineer and inventor, is perhaps her most well-known contribution to modern lighting technology. Together, they developed a system of colored lights and projectors that allowed Fuller to change the color and shape of her costumes in real-time, creating a dazzling effect that captivated audiences.

This system, which used electric arc lamps and colored glass filters, was far ahead of its time and required a significant amount of technical expertise to operate. Fuller and Tesla worked tirelessly to perfect the system, which was used in a number of her most famous performances, including “Serpentine Dance,” “Butterfly Dance,” and “Fire Dance.”

The Serpentine Dance, which Fuller performed to great acclaim in the 1890s, was particularly innovative in its use of lighting. Fuller used a series of long, flowing garments made of silk and chiffon that were illuminated from behind with colored lights, creating a mesmerizing effect as she moved across the stage. The dance was a sensation and helped establish Fuller’s reputation as a groundbreaking artist and pioneer of modern lighting technology.

Fuller’s use of lighting wasn’t just limited to her performances, either. She was also an inventor in her own right, and developed a number of lighting-related inventions over the course of her career. In 1901, she patented a device called the “Fuller Dipsy Doodle,” which was a portable electric light that could be used for a variety of purposes, including stage lighting and photography.

Overall, Loïe Fuller’s contributions to modern lighting technology were groundbreaking and far ahead of their time. Her collaboration with Nikola Tesla and her own inventions helped to establish her as a true pioneer in the field, and her legacy continues to inspire artists and engineers to this day.

Only surpssed by Sarah Bernhardt

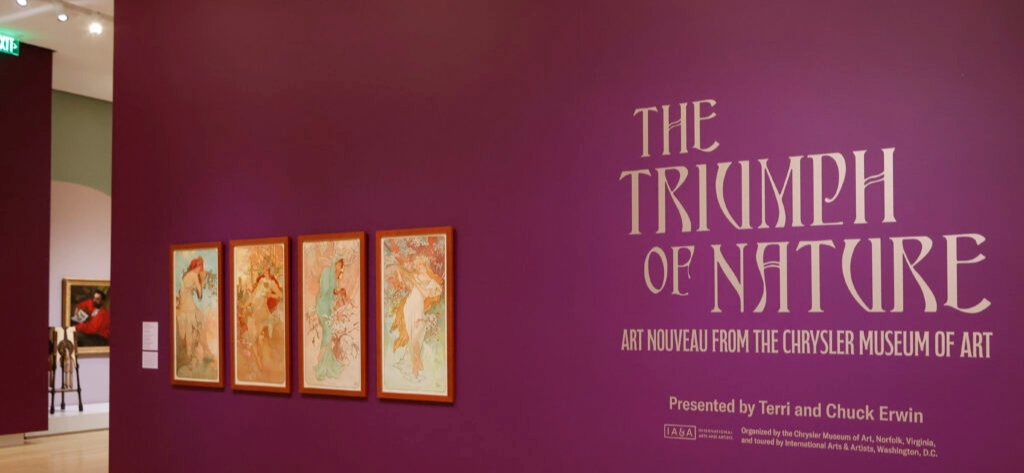

From all the Ladies of Paris, art nouveau muses, the most popular one was Sarah Bernhardt the divine, who was discovered by Alphonse Mucha.

She used to be the first diva and best actress of the world and was Mucha‘s muse for a long time. Her fabulous life is explained during the itinerary of our Art Nouveau Parisian private tour: CLICK HERE for more information.

Stay updated with Art Nouveau events and tours on artnouveau.club. Have a related event or news to share? Send details to contact@artnouveau.club so we can spread the word!