From August 16 to October 5, 2025, the Petersberg Museum in the town of Petersberg, near Halle, will host “Jugendstil—The Aesthetic Movement,” a special exhibition featuring exquisite works of art from the Art Nouveau period. The collection includes magnificent bronze sculptures, as well as everyday objects and home accessories made from ceramics, pewter, glass, and other materials. As announced by the museum, among the items on display are original pieces by renowned artists such as Archibald Knox, Albin Müller, and Richard Riemerschmied. This impressive private collection has been generously provided by Birgit and Ronny Müller from Halle (Saale). The Petersberg Museum is open daily, except on Mondays, from 10:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m.

The Art Nouveau period, known as Jugendstil in German, flourished from approximately 1890 to 1910. Artists from this era aimed to integrate art into everyday life, believing that art and beauty should be accessible and present everywhere. They argued that while the functionality of handcrafted objects was essential, their aesthetic appeal should not be neglected. The goal was for these pieces to bring joy to both the craftsman who created them and the consumer who used them. Jugendstil can be seen in the furniture design, architecture, painting, sculpture, and the production of jewelry and glassware from this time. Its charm and enduring appeal remain fresh and timeless for many people today.

For more information on this exhibit, click HERE.

Jugendstil in Germany: Forging a Modern Style in Interior Design and Architecture

Art Nouveau, an artistic movement that flourished in Europe and America between 1890 and 1910, or up until the eve of the First World War in 1914, represented a powerful reaction against the predominant artistic norms of the late 19th century, specifically academism, eclecticism, and historicism. Artists and designers sought a “new art” that would reflect the modern era and break with the conventions of the past. In Germany, this style was primarily known as Jugendstil.

The term Jugendstil, which means “youth style” or “style of the youth,” became popular in Germany because of the influential Munich art magazine Die Jugend, which was founded in 1896. Other names used in the region included Wellenstil (“wave style”) or Lilienstil (“lily style”). This name, along with the publication of Ver Sacrum in Vienna, symbolized the desire of Vienna Secession artists to express their independence from German influence. The concept of “die Moderne” had already appeared in German discourse in 1886 in a Berlin literary magazine, anticipating the search for a style appropriate for modern life and the modern metropolis.

German Jugendstil, as part of the Art Nouveau movement, was characterized by a distinctive aesthetic. Nature was its most significant source of inspiration, manifesting in decorative designs with tendril-like, bold, sinuous, rhythmic, energetic, and organic curved lines, often described as “whiplash lines.” Botanical and zoological motifs, such as flowers, plants, and insects, were ubiquitous. While early floral Jugendstil initially immortalized the use of curvilinear elements, toward the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th, some Jugendstil centers began to take a stance against the excesses of the curvilinear approach. This led to a greater inclination toward geometric severity, with more abstract and reduced forms, straight lines, right angles, symmetrical structures, and a strong emphasis on the contrast of light and shadow.

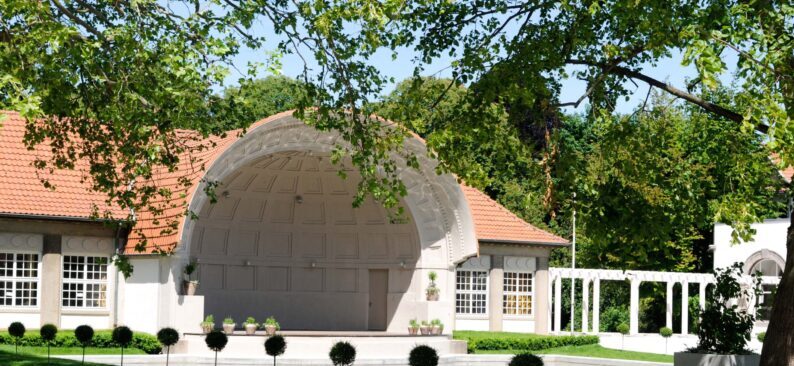

A central ideal of Art Nouveau, including Jugendstil, was the creation of a “total work of art” (Gesamtkunstwerk). This meant that all elements of a space—from the architecture to the furniture, lighting, textiles, and decorative objects—had to merge into a harmonious and cohesive style, seeking an interrelationship in design. Jugendstil also used a variety of innovative materials and techniques. Architects explored the application of different plaster textures to create decorative accents on facades, using a diversity of materials such as plaster, brick, and ceramic tiles. The production of plaster patterns and prefabricated Roman cement elements was also characteristic. Architectural compositions often blended classical and Renaissance components (such as hierarchically ordered floors and pilasters) with medieval, Gothic, and Baroque references. The roofs of buildings frequently alluded to the towers of castles or the shape of thatched roofs. In early Jugendstil, there was an emphasis on flat surfaces with large curvilinear ornaments.

Several artistic centers and designers stood out in the development of Jugendstil. Munich and Darmstadt were major art centers. Munich was home to figures such as Otto Eckmann, Hermann Obrist, August Endell, Richard Riemerschmid, Bruno Paul, Bernhard Pankok, and Peter Behrens, who formed the nucleus of a group of young artists dedicated to the applied arts. Darmstadt was another important center, known for the Darmstadt Artists’ Colony Exhibition in 1901. August Endell designed the Atelier Elvira in 1897 in Munich, considered the most striking example of Art Nouveau in Germany, notable for its use of flat surfaces. His Buntes Theater in Berlin, four years later, also showed clear connections to Art Nouveau. Other designers included Gustaf Wickman, who designed the Enskilda Bank of Norrköping with a floral facade, and Alfred Grenander, known for the curved supports of bridges for the Berlin subway. Paul Leschke in Brunswick and Heinrich Raabe in Cologne ran industrial design studios that sold their creations to manufacturers in Germany, France, and England.

The Jugendstil in Germany was more than a simple aesthetic style; it was an expression of the search for modernity and national identity. It arose as a reaction against academic art, eclecticism, and 19th-century historicism. German artists felt a great moral responsibility in creating objects of fine craftsmanship and individual value to counteract the cheap products of a degraded mass culture, repudiating academic conventions and ingrained historicism. It received influences from the British Arts and Crafts Movement, Japonism (with its minimalist drawing style and reverence for nature), and Gothic and Baroque forms in architectural composition. From the beginning, German Jugendstil had a side of national romanticism, with the goal of contributing to the imagery of a nation-state. It sought a “historically free” style that would appeal to the growing upper-middle class.

Despite rejecting previous styles, there were strong links between Jugendstil and Expressionism. Both were inspired by nature (although Expressionism abstracted it to a greater degree), supported new materials, criticized mass-produced goods, and shared ideas about an idealized society. Many German painters who later became leading figures of Expressionism, such as Ernst Ludwig Kirchner or Barlach, had their beginnings in Jugendstil.

Despite its notable popularity, Jugendstil was an ephemeral style that began to decline around 1910. It was criticized for being an “excess of ornament and decoration without functional substance.” After 1900, German architects, such as Peter Behrens and Joseph Maria Olbrich, quickly abandoned the style in its more purely decorative form, moving toward a more modern and functional design. Nevertheless, Art Nouveau, including Jugendstil, left an indelible mark on European art and design. It challenged traditional artistic barriers, laying the groundwork for 20th-century modernism. Despite being underestimated for decades, it experienced a resurgence in the 1960s, and continues to generate interest in exhibitions and studies, confirming its lasting appeal and crucial role in the evolution of modern art.

To discover the Top 8 cities in Germany showcasing art nouveau click HERE.

Jugendstil was very popular in countries like Germany or Norway (the pictures above are from Alesund, Norway).