The Art Nouveau movement, known in Germany and Austria as Jugendstil or the “style of youth,” emerged as a significant artistic and architectural force that swept across Europe and beyond between approximately 1890 and 1914. More than a simple decorative trend, this multifaceted movement represented a powerful reaction against the academic, eclectic, and historicist styles prevalent in the 19th century. Its proponents sought to create a “new art” appropriate for the modern age and, in doing so, aimed to create a better environment for people by fundamentally transforming the character of European civilization. Art Nouveau was not merely a singular movement but a dynamic collection of regional styles, all characterized by a new formal vocabulary that broke from historical precedent.

Darmstadt was a pivotal center for the artists’ colony movement, and Bad Nauheim a spa town where the style profoundly influenced its public and leisure architecture, while also detailing the broader characteristics and ongoing preservation efforts associated with this globally appreciated style.

The foundational principles of Art Nouveau, regardless of its regional variations, were deeply rooted in a desire for a holistic and modern aesthetic. A primary wellspring for the style was nature, translated into decorative elements with sinuous, rhythmic, and curvilinear lines, often described with vivid intensity as “whiplash lines.” These energetic, flowing lines were a dramatic departure from the rigid forms of the past, imbuing every object and facade with a sense of life and motion. Botanical and zoological motifs were widely used, reflecting a reverence for nature and an interest in biological forms and optimal organizational structures. Artists like Emile Gallé in Nancy, a center for horticultural research, meticulously studied plants, flowers, and insects using photography for his glass designs, illustrating how nature was directly integrated into artistic creation. This translation of nature into art often involved a process of abstraction by reduction and simplification, moving from complexity to simplicity while retaining the essence of natural rhythms and organic growth. The deliberate use of line and color, and the geometric arrangement of forms in a flattened space, were key to stimulating predetermined emotions and creating a new visual language.

A defining ideal of the movement was the Gesamtkunstwerk, or the “total work of art,” where all artistic elements within a space—from architecture to furniture, lighting, and decorative objects—were harmoniously integrated to form a unified aesthetic. This holistic approach extended to the very structure and ornamentation of buildings, aiming for every element, both externally and internally, to be in aesthetic harmony. While this concept has historical precedents, from Historicist constellations of structures like the Vienna Ringstrasse to grand houses of the past, its application in Art Nouveau was radical. It meant that the entire building was subordinated to an ornamental concept that integrated every part into a cohesive vision, considering each structural or decorative component as intrinsically linked to the overall artistic whole. It was a moral and creative response to the perceived soullessness of mass production, an ambitious attempt to unify art, craft, and daily life into a single, beautiful experience.

Material innovation and construction techniques were also central to Art Nouveau architecture. Architects enthusiastically experimented with various plaster textures, brick, ceramic tiles, and Roman cement to create distinctive decorative accents on facades. There was a significant shift from painting plasterwork, a common practice in the 19th century, to valuing the natural visual quality of unpainted materials for contemporary buildings by 1900. This led to a rich variety of finishes such as rough-cast, combed plasterwork (applied in various techniques and consistencies), or “squeezed” plaster, achieved through pressure and suction. These innovative surface treatments, along with the combination of different materials, decisively shaped the character of the facades in Austrian Art Nouveau architecture, transforming simple materials into integral ornamental design elements. The exteriors became a living canvas, where textures and natural colors created a dynamic interplay of light and shadow, giving buildings a unique, handcrafted feel despite their modern construction.

The Belle Époque, a period of “unprecedented economic, technical, and social progress,” spurred a demand for modern and sophisticated public buildings. Leading architects like Otto Wagner advocated for a new architecture suitable for the “modern metropolis,” believing that such a city required a fresh, new aesthetic reflecting its dynamism and efficiency. This quest for modernity was also a reaction against the “monotonous and boring” identical facades of the Second Empire and the “architectonic lie” of interest-bearing blocks. Modern architecture was seen as illustrating the “spirit of the times,” focusing on usefulness, comfort, and health requirements, embodying a new “objectivity” or Sachlichkeit. Wagner understood that motorized transportation and the new urban scale led to an “irreversible psychological mutation,” requiring a new aesthetic tailored to a “swiftly moving eye” that could take in vast panoramas at a glance. This resulted in a push for simplified facades and diminished ornament, a concept that would later influence the geometric phase of Jugendstil.

Darmstadt holds a special and pivotal place in the history of the Art Nouveau movement in Germany. Its significance is intrinsically linked to the establishment of its renowned Artists’ Colony at Mathildenhöhe. In 1899, Grand Duke Ernst Ludwig of Hesse initiated this ambitious project by inviting young artists to live and work together in Darmstadt. This collective, communal approach was instrumental in fostering the collaborative spirit so essential to the Gesamtkunstwerk ideal. Among the notable artists who joined the colony were: Joseph Maria Olbrich, originally from Vienna, where he had designed the iconic Vienna Secession building in 1898, and Peter Behrens, from Munich. Olbrich’s involvement brought a distinctive Austrian Secessionist flavor to the German context, characterized by a certain geometric rigor. The colony’s impact was showcased prominently at the “Exhibition of the Artists’ Colony in Darmstadt” in 1901, also known as “Ein Dokument Deutscher Kunst” (A Document of German Art), which featured banners designed for Behrens’s house. The Mathildenhöhe Darmstadt Artists’ Colony is specifically recognized as a World Heritage Site, a testament to its profound cultural value as a living laboratory for modern design.

The broader context of German Jugendstil saw it developing distinct characteristics. While some international Art Nouveau styles, like the French and Belgian, emphasized curvilinear ornament, the German and Austrian Jugendstil (or “Secessionsstil”) often moved towards an emphasis on flat surfaces, later reducing or entirely abandoning large-scale curvilinear decoration. The popular Munich magazine Jugend lent its name to the German iteration of the style, “Jugendstil.” Figures like Peter Behrens and Hermann Obrist were instrumental in shaping German Art Nouveau, which, like other regional styles, incorporated local specificities. Berlin also emerged as an important center, and museum directors in industrial towns like Hamburg and Krefeld promoted the “New Style.” Henry van de Velde, another prominent Jugendstil artist associated with the period, later directed the Weimar School for Arts and Crafts, a direct precursor to the Bauhaus. The German Secession Style itself is defined by a clean, basically geometric ornamental vocabulary, even though initial characteristics included vegetal and floral motifs that were contained within specific limits.

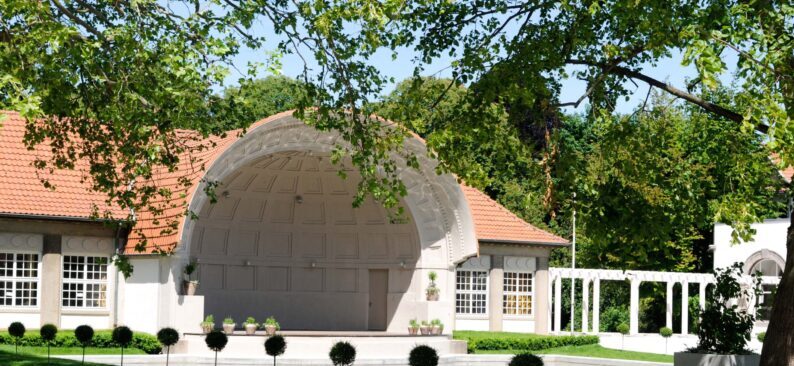

Bad Nauheim significantly influenced by Art Nouveau, or Jugendstil, given its status as a prominent spa town during the movement’s peak period (1890-1914). Art Nouveau was a style that permeated various aspects of life, including public and leisure architecture. The Belle Époque saw a substantial segment of construction dedicated to buildings like spas and casinos, catering primarily to the bourgeois class and reflecting a demand for modern and sophisticated public spaces. A spa complex, by its very nature, focuses on health, wellness, and a connection to nature, themes that align perfectly with the core tenets of Art Nouveau. The movement’s deep connection to natural forms and the aspiration to create a healthier, more natural environment would have provided a rich decorative vocabulary for a spa, incorporating intricate carvings, mosaic patterns, stained glass, or frescoes depicting natural motifs that both soothe and inspire. Such a complex would represent an ideal opportunity for the creation of a Gesamtkunstwerk, where every aspect, from the architectural layout of bathhouses to interior furnishings and decorative arts, would be conceived as a unified, harmonious whole, prioritizing both aesthetics and practical, functional solutions for the comfort of its visitors.

Consistent with Jugendstil trends observed in Austrian architecture, a spa complex in Bad Nauheim would likely have showcased a rich variety of materials and finishes. Facades could have featured diverse plaster textures—rough-cast, combed, or squeezed—alongside intricately patterned ceramic tiles and Roman cement elements. The emphasis on the natural visual quality of these materials, rather than painted surfaces, would have been a hallmark of the design, reflecting the movement’s push for “constructive truth.” Furthermore, as a rapidly developing city, Bad Nauheim’s spa complex would have been designed not just as an individual building, but as an integral part of the town’s urban fabric, contributing to a “fresh, pulsating life” and aligning with broader debates on city planning and the creation of new urban experiences. Its presence would have contributed to the desired “aesthetic of modernity” and sophisticated representation of the metropolis, making it a destination that was both a place for healing and a total work of art.

Both Darmstadt, with its historically documented Artists’ Colony at Mathildenhöhe, and Bad Nauheim, with its implied architectural legacy as a Belle Époque spa town, stand as significant, albeit different, examples of the Art Nouveau/Jugendstil movement in Germany. Darmstadt concretized the movement’s ideals of artistic collaboration and innovation under ducal patronage, showcasing a modern artistic expression in architecture and design. Bad Nauheim, while not directly detailed in the sources, would have naturally embraced Art Nouveau’s principles in its public leisure architecture, integrating art with daily life, celebrating nature, and creating aesthetically unified and modern environments for well-being. The enduring legacy of these and countless other Art Nouveau sites across Europe is actively supported by organizations like RANN, which strive to preserve this vibrant, dynamic, and profoundly influential period of architectural and artistic history for future generations, ensuring its cultural and historical value continues to be recognized and understood.