Art Nouveau emerged in the late 19th century as a worldwide phenomenon, marking a pivotal moment in European culture by introducing a “new art” that sought to break away from the academic, eclectic, and historicist styles prevalent in the 19th century. This movement aimed to revitalize handicrafts, which had seen diminished attention with the advent of the Industrial Age, under the democratic slogan of “Art for everyone/Art in everything”. Although it was a short-lived style, flourishing primarily between 1890 and 1914, ending abruptly with the onset of World War I, its impact extended far beyond architecture, profoundly influencing various forms of design, fashion, and daily life.

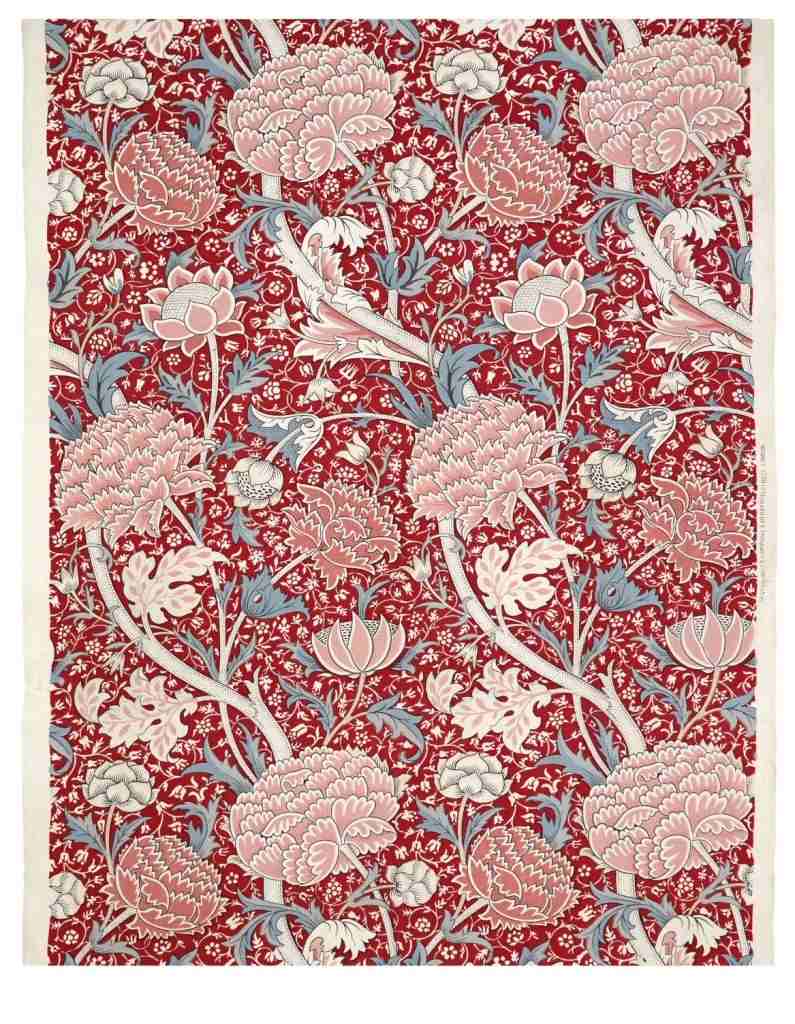

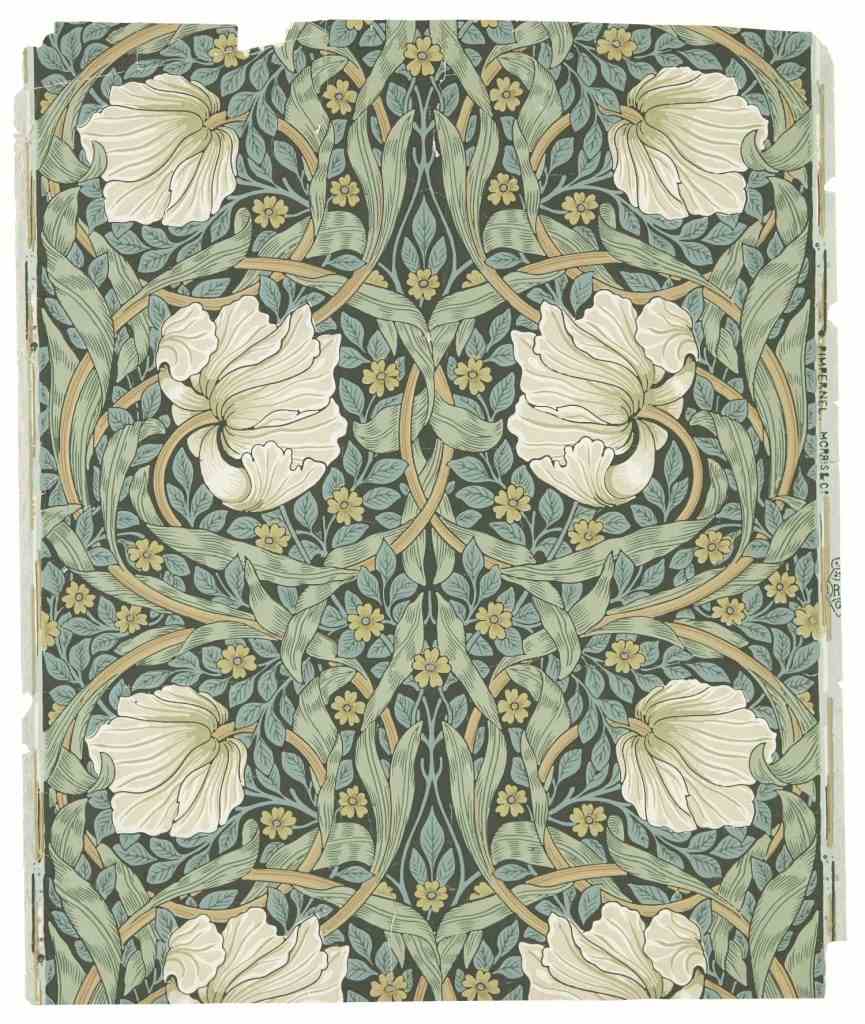

At its core, Art Nouveau was characterized by a distinctive aesthetic embracing organic and curved forms, frequently featuring sinuous curves and floral motifs inspired by the natural world. This organic influence manifested in tendril-like, bold, rhythmic, springing, energetic, and asymmetrical lines, often referred to as “whiplash” curves or lines. The movement intentionally rejected the rigid, straight lines of classical and historicist architecture, recognizing that nature is full of curved forms, not straight lines. Beyond its visual characteristics, Art Nouveau artists sought a Gesamtkunstwerk, or “total work of art,” aiming to unify all artistic expressions within a single environment, from structural elements to interior furnishings and everyday objects. This holistic approach meant that Art Nouveau was not confined to monumental buildings but permeated the fabric of daily existence, making beauty and art accessible in practical items.

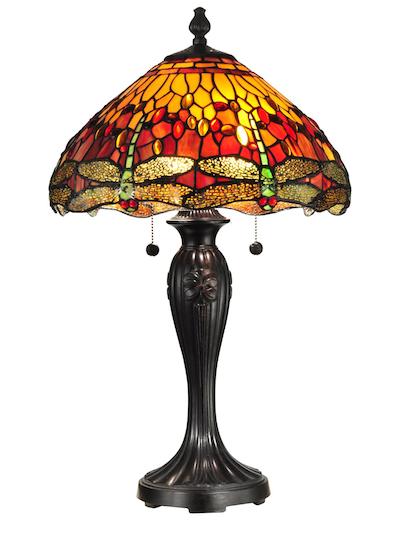

The influence of Art Nouveau was particularly profound in the decorative arts and everyday objects, where its principles aimed to imbue even the most mundane items with aesthetic value. Designers sought to integrate decorative and industrial arts, readily incorporating new materials and construction techniques such as iron, glass, and ceramics. This period saw the creation of a vast array of Art Nouveau products, transforming daily items into works of art. For instance, Gustave Gurschner crafted bronze bowls and brooches with Art Nouveau sensibilities around 1900. Emil Galle, a prominent figure in the Nancy School, was celebrated for his artistic glassware, while Daum Frères produced exquisite cameo vases. Louis Comfort Tiffany also gained renown for the technical virtuosity and fluidity of his glassware, including Favrile ware and gooseneck sprinklers. These innovations in glass design were often influenced by Japanese stylization and local flora. In furniture, designers like Louis Majorelle, whose buffet from around 1900 is a notable example, and Émile Gallé, created eclectic works intended to harmonize within an overarching design concept. The Glasgow School of Art building by Charles Rennie Mackintosh also showcased his distinctive furniture, such as high, straight-back chairs and his iconic rose design, which used a long global curve ending in a small focal point. The period also saw the introduction of glazed clay and ceramic ornaments into architectural and interior design, often hand-crafted and unique to individual buildings. The integration of artificial lighting into design also became a feature, with flowing floral electric light fixtures being a prime example.

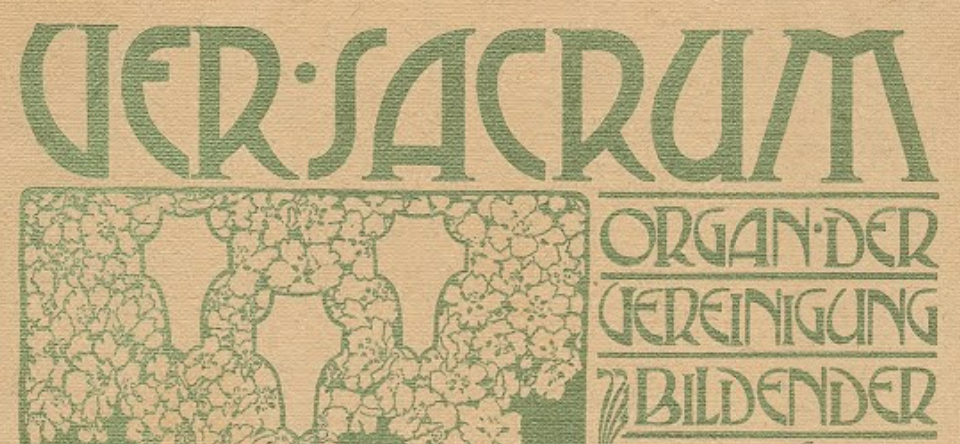

Graphic design emerged as a powerful medium for disseminating Art Nouveau, thanks to advancements in printing technologies, particularly color lithography, which enabled the mass production of vibrant posters. This meant that art was no longer limited to galleries and museums but filled the streets of cities like Paris and circulated widely through illustrated art magazines across Europe and the United States. Women, symbolizing glamour, modernity, and beauty, often surrounded by flowers, were a popular theme in Art Nouveau posters. Alphonse Mucha, a Czech artist, revolutionized poster art, making it accessible to a wide audience. His famous works include advertisements like the enticing 1897 poster for Job cigarette paper and the Gismonda poster for Sarah Bernhardt. Mucha’s Documents Décoratifs also demonstrated his decorative designs. Siegfried Bing, a German-born art collector and dealer, played a crucial role in popularizing the style through his gallery, Maison de l’Art Nouveau in Paris, which opened in 1895 and lent its name to the movement. He showcased diverse works, including stained-glass windows produced by Louis Comfort Tiffany based on designs by colorist painters. Art magazines such as Jugend in Germany (which gave the style its German name, Jugendstil) and Pan significantly contributed to the spread of Art Nouveau across Europe.

The reach of Art Nouveau even extended into the realm of fashion. The style’s emphasis on organic, flowing lines and decorative imagery found a natural fit in garment design. Contemporary designers continue to draw inspiration from Art Nouveau’s forms, colors, and aesthetics in their collections. Notable designers whose works have been influenced by Art Nouveau include L Wren Scott, Anna Sui, Parada, Gucci, Tory Burch, Alexander Mc Queen, Alberta Ferretti, and Rodarte. For example, Parada’s Spring RTW 2008 collection featured designs with Art Nouveau-inspired tendrils. The movement’s principles, particularly its “whiplash flow,” were key motifs in fashion. Decades later, Art Nouveau experienced a significant resurgence in the 1960s, deeply influencing American culture and the emerging hippy aesthetic, with its motifs appearing in clothing, furniture, and posters of that era.

Despite its relative brevity and eventual decline due to factors such as its high cost and the rising preference for geometric abstraction and nationalism, Art Nouveau established a crucial transitioning bridge between 19th-century historicism and 20th-century modernism. It challenged traditional artistic boundaries, emphasizing the unity of the arts and applying aesthetic principles to all aspects of life. This “new art for a new century” sought to create better lifestyles by focusing on beauty, functionality, and the connection with nature. Art Nouveau’s enduring legacy is seen in its fundamental role in reshaping the relationship between art, craft, and industry, and its aesthetic qualities continue to be appreciated in many contemporary designs, from chairs and doorknobs to jewelry and graphic art. The renewed interest in Art Nouveau since the 1960s, evidenced by numerous exhibitions and scholarly works, underscores its lasting importance and its pioneering contribution to modern design.

Art Nouveau, with its distinctive organic forms and pervasive influence, is a movement best experienced firsthand. While books and online resources offer valuable insights into its history and characteristics, they can only provide a limited sense of the immersive beauty that defines this “new art.” The true essence of Art Nouveau lies in its ability to transform everyday environments into holistic works of art, where every detail, from the grand architectural lines to the smallest decorative element, is part of a unified aesthetic vision. Seeing the sinuous curves of a building’s facade, the delicate craftsmanship of a stained-glass window, or the intricate design of a doorknob in person allows for an appreciation of the movement’s commitment to integrating art into all aspects of life, something a two-dimensional image simply cannot convey. It’s in the way light interacts with a Tiffany lamp, the texture of an Émile Gallé vase, or the sheer scale of a Charles Rennie Mackintosh interior that the depth and ambition of Art Nouveau truly come alive. For a deeper dive into the movement’s core, you might enjoy reading about “Art Nouveau: The organic heartbeat of a global movement”.

Furthermore, exploring Art Nouveau in its original context allows one to grasp its “total work of art” concept more profoundly. The harmonious interplay between a building’s structure, its interior furnishings, and even the everyday objects within it is a fundamental aspect of the style. Imagine walking into a space where the staircase railings mirror the motifs on the wallpaper, and the light fixtures echo the floral patterns on the furniture. This level of integrated design creates an unparalleled sensory experience that simply cannot be replicated by studying photographs or descriptions. The subtle nuances of color, the play of light and shadow on curved surfaces, and the sheer craftsmanship of the period are best appreciated when standing within these magnificent spaces, allowing the intricate details to unfold before your eyes. It’s like stepping into a living painting, where every element contributes to a singular, breathtaking vision. Ever wondered how Art Nouveau differs from its successor? Test your knowledge with “Can you distinguish Art Nouveau and Art Deco?”.

To truly unlock the magic of an Art Nouveau city, a knowledgeable local guide is invaluable. Unlike generic tour guides or static guidebooks, a guide passionate about Art Nouveau can illuminate the subtle details, hidden meanings, and fascinating stories behind each masterpiece. They can point out the influence of local flora on a building’s ornamentation, explain the significance of a particular “whiplash” curve, or share anecdotes about the artists and patrons who shaped the movement in that specific location. Their enthusiasm and in-depth knowledge elevate the experience from a mere sightseeing trip to an engaging journey of discovery. Friends might offer recommendations, but a dedicated Art Nouveau expert can provide the context and depth of understanding that transforms a casual observation into a profound appreciation. Did you know, for example, that many Art Nouveau artists drew direct inspiration from microscopic organisms and natural growth patterns, creating designs that feel both alien and deeply familiar? You might also be surprised to learn about “The 40 different names of Art Nouveau” used across different countries!

The “Art for everyone/Art in everything” ethos of Art Nouveau is most powerfully felt when you can interact with its manifestations in the urban landscape. It’s about recognizing the artistic intent in something as common as a metro station entrance or a shopfront. This widespread presence means that the experience of discovering Art Nouveau is inherently interactive and immersive. Whether it’s the iconic metro entrances of Paris, the fantastical buildings of Barcelona, or the elegant townhouses of Brussels, each city offers a unique Art Nouveau narrative. To truly immerse yourself in this rich artistic heritage and uncover its countless treasures, a personalized approach is often best. At artnouveau.club, we pride ourselves on our 100% satisfaction record for private tours in many cities, ensuring an unforgettable and deeply enriching Art Nouveau experience.