In a significant development for art and architectural enthusiasts, a rare collection of buildings designed by the renowned architect Charles Rennie Mackintosh is slated to be sold. The Mackintosh Halls, located on Shakespeare Street in the Ruchill area of Glasgow, were purpose-built in 1899 for the Church of Scotland and stand as one of the architect’s most distinctive early works. After more than 120 years, the Church has confirmed that the site will be placed on the market later this year, though the guide price has yet to be disclosed.

This decision comes in the wake of the 2022 union of the Ruchill Kelvinside and Maryhill congregations. According to Reverend Stuart Matthews, the minister of the newly formed Maryhill Ruchill Church, the choice to sell was not made lightly. “We have looked after the Mackintosh Halls for many years,” he explained, “but like the wider Church of Scotland, we face challenges of declining congregations, financial constraints, and the lasting impact of the pandemic.” He expressed hope that a new owner with “greater resources will recognize their importance and secure their future.”

However, the announcement has been met with sadness and disappointment from the local community. Residents believe the sale will be a “big loss,” and David Glenday, who lives in nearby Wyndford, described the news as a “thunderbolt from a clear blue sky.” He said, “It’s a very valued site. There used to be a Friday lunch club, which was great… We were very disappointed to hear that the Church of Scotland were going to sell the buildings, and this would all come to an end.”

The site’s architectural significance is immense. The buildings, which are A-listed, include a large meeting space and a janitor’s house, and were designed around the same period as Mackintosh’s celebrated Glasgow School of Art and the nearby Queen’s Cross Church. A later addition to the site—a church sanctuary by architect Neil Campbell Duff—is B-listed but is not an original Mackintosh design. Reverend David Gray, who serves as the property convenor of the Glasgow Presbytery and is also an architect by training, emphasized the site’s historical value. “This is a rare surviving example of Mackintosh’s early work, reflecting his evolving style in the years leading up to the Glasgow School of Art,” he stated. “The Mackintosh Halls embody many of the ideas that came to define his career and represent an important cultural asset to be preserved.”

Inside, the halls are a true showcase of Mackintosh’s developing style. They feature the trademark Art Nouveau flourishes and “art nouveau motifs scattered throughout the building” that would become synonymous with his work. Visitors can admire the unique stained glass windows, elegant curvilinear lines, and stylized floral motifs that define his aesthetic. Stuart Robertson, director of the Charles Rennie Mackintosh Society, highlighted the halls’ place in the designer’s formative creative period, which spanned from 1895 to 1906. “The Ruchill Halls display Mackintosh’s signature style, echoing the work seen in Queen’s Cross Church, the Glasgow School of Art, and his early commissions for Miss Cranston,” he noted. The Glasgow School of Art was tragically almost completely destroyed by two fires in 2014 and 2018.

The sale of these halls presents a unique opportunity and a considerable challenge. Preserving the A-listed structures requires specialized knowledge and significant investment. The hope among preservationists and the local community is that a buyer will be found who not only appreciates the artistic and historical value of the buildings but is also committed to their long-term conservation, ensuring that this vital piece of Glasgow’s architectural heritage remains for generations to come. This comes after Glasgow City Council sold a former school also designed by Mackintosh earlier this year, which is set to become a Scottish Catholic museum.

Full information at this interesting article with many pictures from the buildling, from The Herald.

Glasgow and Charles Rennie Mackintosh

The Art Nouveau movement, which emerged at the end of the 19th century and flourished until the early 20th century (approximately 1890-1914), represented a powerful reaction against the academic art, eclecticism, and historicism that dominated the artistic landscape of the era. Artists and designers sought a “new art” that would reflect the modern age and break from past conventions. Their slogan, “Art for all / Art in everything,” promoted the applied arts as a fundamental principle of design. This democratic movement profoundly impacted both Europe and America, aiming to capture the relationship between art, craftsmanship, and industry with a contemporary focus.

Art Nouveau was characterized by decorative designs featuring sinuous, rhythmic, organic, and asymmetrical lines that often resembled plant stems and flowers. A central tenet was the ambition to transcend the traditional hierarchy between fine and applied arts, striving for a “total harmony” where all elements, from painting to furniture, functioned in a unified manner. This concept was known in Germany as “Gesamtkunstwerk”. While the style manifested with distinct national characteristics and under various names—such as Secession in Vienna, Jugendstil in Germany, Stile Liberty in Italy, or Modernismo in Catalonia—Glasgow emerged as a vital center for Art Nouveau architecture and furniture design in Great Britain. Paul Greenhalgh identified three core sources from which the essence of Art Nouveau emerged: History, Nature, and Symbolism. The appreciation and study of the natural world were crucial, with books featuring “magnificent illustrations of cellular life” and the increase of “conservatories and hot houses in the public parks of Brussels, London, Paris, Vienna, and other cities”.

The Glasgow Style and “The Four”

Art Nouveau in Glasgow found its distinctive expression through the “Glasgow Style,” spearheaded by a group of artists known as “The Four”. This influential group comprised architect Charles Rennie Mackintosh, his wife, painter and glass artist Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh, Margaret’s sister Frances Macdonald, and Herbert MacNair, who married Frances.

“The Four” forged a fusion of influences, including the Celtic Revival, the Arts and Crafts movement, and Japonisme, which gained significant recognition in continental European modern art circles. Their work was initially derided as the “Spook School” or “Ghoul School” due to its “distorted and conventionalized” human forms. Distinctive motifs of the Glasgow Style included stylized eggs, geometric forms, and the “Glasgow Rose”. In contrast to the exuberant curves of the “whiplash line” often seen in the work of artists like Aubrey Beardsley, Mackintosh’s style employed linear rhythms characterized by a “measured austerity”. In his two-dimensional works, such as prints and paintings, Mackintosh also emphasized the flattening of space and the consequent importance of the surface. The progressive environment at the Glasgow School of Art facilitated the flourishing of women artists in Glasgow, including Margaret and Frances MacDonald and Bessie MacNicol, during an “enlightenment period” between 1885 and 1920. The “Glasgow School” had a considerable influence on the Viennese art scene.

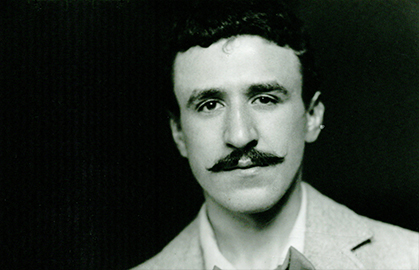

Charles Rennie Mackintosh: A Pioneer of Modern Architecture

Charles Rennie Mackintosh (1868-1928) was the “most powerful and imaginative personality” to emerge from the Glasgow group. His work, along with that of his wife Margaret, proved influential in European design movements, Art Nouveau, and the Vienna Secession.

Mackintosh’s design philosophy was characterized by combining geometric straight lines with soft floral decoration and delicate curves. His furniture often displayed an elongation in design. Notable among his creations are:

• The Glasgow Herald Building (1894), which later became The Lighthouse, Scotland’s Centre for Design and Architecture.

• The Glasgow School of Art (1897-1909): This institution stands as one of Mackintosh’s seminal works. Its reputation and influence were continuously evaluated. The building tragically suffered two devastating fires: one in May 2014 and another in June 2018, the latter completely destroying the building and the restoration work undertaken since the first blaze. The renowned two-story library, a complex and subtle construction almost exclusively in wood, was entirely lost, along with its impressive collection of books and original Mackintosh-designed furniture. Despite the tragedy, the Glasgow School of Art committed to rebuilding the edifice to honor its original architect. Restoration efforts have involved a meticulous analysis of the building’s history, period photographs, Mackintosh’s original drawings, and technical drawings by former students. This detailed information allowed for the creation of a precise digital model of the library, facilitating the construction of a full-scale prototype of one of the lost bays. Scientific research revealed that the original timbers (primarily tulipwood) had been stained with oil paint and then rubbed with beeswax, with a burnt sienna color being the closest match, though it was recognized that the original color had darkened over time due to air pollutants and tobacco use. The library’s lights, initially overpainted, were reconstructed with their original aged brass finish. The reopening of the restored Mackintosh Building in 2019 was anticipated as a significant event, reflecting the school’s commitment to achieving the most authentic look possible.

• The Willow Tearooms (1903): Mackintosh designed these tearooms for entrepreneur Catherine Cranston, creating an urban oasis with distinct spaces, including a ladies’ room, a general dining area, and the exclusive “Room de Luxe”. An example of his design is a stained-glass window featuring a “long global curve ending in a small-scale focal point, shaped like a rose”. Mackintosh also designed the poster for the Scottish Musical Review in 1896.

Mackintosh’s architectural career was relatively short, but he also dedicated himself to furniture and interior design. Later in life, he moved to Port Vendres, France, to pursue watercolor painting.

Legacy and Influence of Art Nouveau

Despite limited popularity in Great Britain, Mackintosh’s work garnered considerable recognition on the European continent. He directly influenced artists like Gustav Klimt and the Vienna Secession after being invited to exhibit at the 8th Secession Exhibition in 1900. His artistic development was noted as being “parallel and divergent from Art Nouveau,” which presented a challenge for critics and historians, as his influence on the continent from 1900 onwards contrasted with the continued evolution of Art Nouveau in architecture.

The Art Nouveau movement, though relatively brief, left an indelible mark on European art and design, challenging and breaking traditional artistic boundaries and paving the way for 20th-century modernism. Renewed interest and re-evaluation of Art Nouveau in recent decades, evidenced by exhibitions and academic studies, underscore its enduring appeal and crucial role in the evolution of modern art. The Réseau Art Nouveau Network works to attract attention to the European and universal value of Art Nouveau heritage, noting that many creations remain unknown or unprotected. June 10th is celebrated as World Art Nouveau Day, an event coordinated by the Réseau Art Nouveau Network, dedicated to preserving and promoting this valuable European cultural heritage.

Beyond Glasgow, other key figures of Art Nouveau include Otto Wagner, whose Postsparkasse and Länderbank in Vienna are iconic examples of integrating new expressions and engineering achievements. Wagner, a leading figure in modern architecture development, explored modernity and the modern metropolis, advocating for a “realistic architecture” that openly serves its purpose. He emphasized horizontalism, straight lines, and simplicity for modern cities. His Vienna Stadtbahn also reflects this vision, creating a “theater of space” for its viewers. Other notable Art Nouveau artists include Alphonse Mucha for his posters, Hector Guimard for his Paris Metro entrances, and Victor Horta, known for the Hôtel Tassel and Maison du Peuple in Brussels, who used exposed iron structures and embraced the principle of honesty in architecture.