The Art Nouveau movement, flourishing primarily from 1890 to 1914, emerged as a radical departure from the prevailing academic art, historicism, and the rigid aesthetic consequences of the Industrial Era. It sought to revitalize art and craftsmanship, aiming to integrate beauty into every aspect of life, encapsulated by its ambitious goal of a “total work of art” or Gesamtkunstwerk. Central to this revolutionary aesthetic was an unparalleled embrace of organic forms, which became the unifying and most recognizable signature of the style across its diverse international manifestations.

Nature: The Unending Wellspring of Inspiration

Nature served as Art Nouveau’s paramount source of inspiration, adopted with remarkable complexity and depth. Artists viewed the natural world as a model for transformation and metamorphosis, seeking to represent its inherent dynamism and vital force rather than merely copying antique forms. This profound connection to nature was a deliberate choice to infuse art with vitality and a moral dimension.

The natural motifs were diverse and extensively stylized:

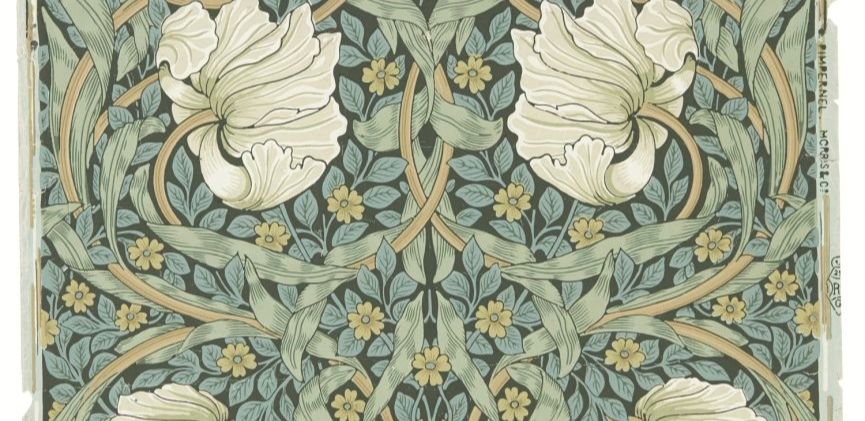

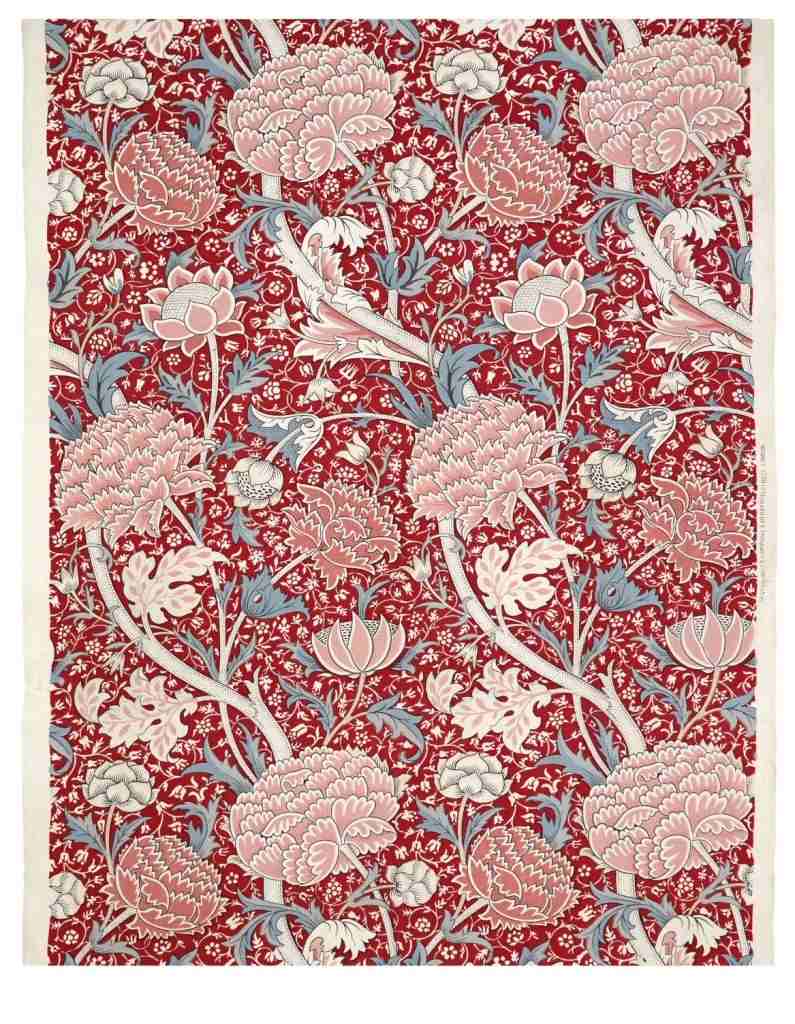

• Flora: The most prevalent representations included the graceful lines of lilies, the intricate patterns of vines, twisting flower stems, and the delicate forms of poppies, chrysanthemums, tulips, orchids, and thistles . These botanical elements were often stylized, flattened into planes of color, and emphasized with strong contours.

• Fauna: Insects like dragonflies, bees, butterflies, moths, cicadas, grasshoppers, and ornate birds were common, as were beetles with spiraling antennae and legs. For example, Émile Gallé’s “pedestal table with three dragonflies around 1900” intensifies the insect’s form to the point of the grotesque, demonstrating this focus3. René Lalique’s dragonfly corsage ornament (1897-1898) similarly showcases the insect form with meticulous detail.

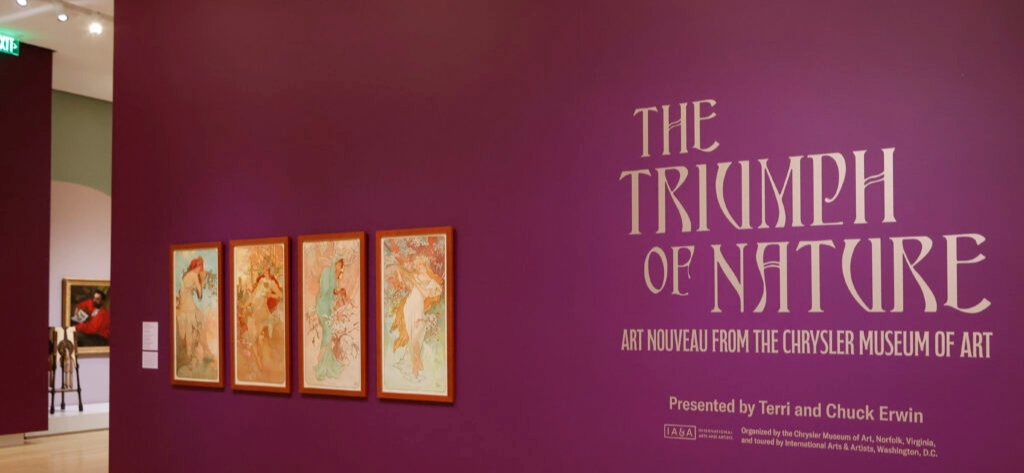

• The Female Figure: Delicate, sinuous female figures were frequently depicted, often with long, flowing hair intertwined with plant stems and flowers, further blurring the lines between human and natural forms. Alphonse Mucha’s works, particularly his posters like “Job” (1898), are replete with these sinuous female figures, floral iconography, and curvilinear forms, often emphasized with heavy black lines that allow the figures to stand out against detailed backgrounds.

Beyond local flora and fauna, Art Nouveau artists were significantly influenced by non-Western art, particularly Japonism. The clear lines and flat areas of color, devoid of traditional perspective, characteristic of Japanese woodblock prints (Ukiyo-e), deeply fascinated European artists and found their way into Art Nouveau designs. Influences also extended to the complex “arabesque” designs of the Middle East and ancient European forms such as Celtic decoration.

Characteristic Organic Forms and Lines

The quintessential characteristic of Art Nouveau was the “whiplash line”. This dynamic, decorative line appears to possess a life of its own, twisting and coiling with a powerful, often asymmetrical rhythm, as if striving for liberation from constraint. This free-flowing arabesque line is widely regarded as a fundamental element of the style.

Other notable organic forms and stylistic features included:

• Sinuous, Rhythmic, and Asymmetrical Curves: These were omnipresent in architecture, painting, and sculpture. Asymmetry, while more common in ornamentation, also informed the volumetric composition of buildings, often drawing inspiration from the organic growth of medieval townscapes over time.

• Circular, Parabolic, and Crescent Forms: These geometries echoed natural shapes and movements.

• Non-Parallel Displacement and Spirals: These were often used to conclude lines or curves, creating a dynamic visual effect.

• Active Surfaces: The surface of an object or building was no longer merely a support for decoration but played an active, integral role in the overall design.

• Vibrant Color Palette: Bright colors such as peacock blue and sea green often replaced the subdued grays and browns of previous styles. A selective palette, sometimes including desaturated warm tones, was used to evoke a sense of romance and fantasy.

The Gesamtkunstwerk: A Total Work of Art

Art Nouveau aimed to dissolve the traditional hierarchy between fine arts and applied arts, striving for a “total work of art” (Gesamtkunstwerk). This philosophy meant that architects, designers, and artisans collaborated to ensure that buildings, their interiors, and all their decorative elements—including furniture, textiles, and jewelry—adhered to Art Nouveau principles, creating a cohesive and harmonious environment. The movement permeated nearly every artistic and design discipline, from architecture and interior design to painting, furniture, fabrics, graphics, industrial arts, jewelry, and metalwork.

Regional Manifestations and City Examples

As an international and primarily urban phenomenon, Art Nouveau developed diverse local variations, adapting to regional traditions and decorative motifs while adhering to its core principles. The “Secession movement” itself is described as a “worldwide phenomenon that started during the late 19th century”.

Brussels, Belgium: Often considered the birthplace of Art Nouveau, Brussels saw pioneering works by Victor Horta. His Hôtel Tassel (1893) is cited as a foundational Art Nouveau building, characterized by its organic style and dynamic, fluid lines. Horta extensively used an exposed iron structure, applying the principle of honesty in architecture, where ornamentation often suggested a structural role even if it wasn’t load-bearing. The Hôtel Aubecq (1899-1902) synthesized a decade of Horta’s work, featuring a double-triangle plan and hexagonal or octagonal rooms extending from a central, sky-lit vestibule. His Hôtel Van Eetvelde (1895) notably evoked Congolese flora and fauna in its design and decoration. Paul Hankar also played a significant role in the early development of the style.

Paris, France:

◦ Hector Guimard epitomized French Art Nouveau with his exuberant, botanical, and sinuous Métro entrances. His lampposts resembled giant tendrils, and the ironwork twisted into bold curves.

◦ Alphonse Mucha’s posters and illustrations, such as “Job” (1898), are filled with characteristic sinuous female figures, floral iconography, and curvilinear forms. His “Decorative Designs” specifically featured superimposed, curling, and swirling effects of leaves and stems.

Nancy, France: The École de Nancy, formed in 1901, elevated Nancy to a European Art Nouveau capital, with a particular focus on local Lorraine flora, like the thistle.

◦ Émile Gallé, a trained botanist, was central to the movement, creating glassware with intricate floral designs. His works, such as the “pedestal table with three dragonflies,” intensified insect forms.

◦ Louis Majorelle designed furniture with elaborate decoration, marquetry, arabesques, and floral motifs. His Villa Majorelle exemplified the unity of art, featuring fluid forms, decorative patterns, and seamless coordination between interior and exterior elements.

Barcelona, Catalonia (Modernisme): Art Nouveau in Catalonia was known as Modernisme.

◦ Antoni Gaudí is the most celebrated figure, renowned for seamlessly integrating nature into his architectural masterpieces, including the Sagrada Família, Casa Batlló, and Casa Milà. His buildings appear to pulsate with life, incorporating ceramics, stained glass, wrought iron, and carpentry into their designs. He employed irregular forms and whimsical decorative motifs abstracted directly from nature, and also integrated Moorish forms and patterns.

Vienna, Austria (Secession/Sezessionstil): While initially leaning towards more geometric and minimalist forms, particularly in the work of Otto Wagner, the Viennese Secession did not entirely abandon organic elements.

◦ Early Secessionist works featured vegetal and floral motifs, though often more restrained and “domesticated” within clear architectural forms.

◦ Otto Wagner, a leading figure in modern architecture in Vienna, focused on a modern architecture that reflected modern life. His Postsparkasse (Postal Savings Bank) (1904-1906) in Vienna, while showcasing a restrained facade and emphasis on functionality, also subtly employs organic elements in its detailing, which can be interpreted as a semantic narrative within the city.

◦ Gustav Klimt, a prominent Secession artist, created works like the Beethoven Frieze (1902 exhibition), a monumental mural featuring sinuous figures and symbolic elements conveying the “salvation of ‘weak mankind’ through the mediation of art and love”. His paintings, including landscapes, used line, color, and texture to evoke specific moods and feelings.

◦ The Wiener Werkstätte, co-founded by Josef Hoffmann, aimed to produce highly crafted works for a select clientele, emphasizing quality craftsmanship and design.

Germany (Jugendstil): Early Jugendstil was characterized by a more literal inspiration from nature and lush ornamentation. Hermann Obrist’s embroidered tapestry “Cyclamen” (1892), with its dynamic “whiplash” motif, became a seminal image of the movement.

Italy (Stile Liberty/Floreale): This style emphasized floral ornamentation. Cities like Florence, Montecatini Terme, Lucca, and Viareggio in Tuscany display numerous examples of Liberty style private houses, stores, and public buildings. While focusing on floral motifs, the Italian approach often combined these with traditional architectural elements, leading to an eclectic character.

Zagreb, Croatia: As a “peripheral Austro-Hungarian city,” Zagreb saw sporadic Art Nouveau buildings appear around the turn of the 20th century, alongside firmly rooted historicist styles. The National and University Library (today the Croatian State Archives), built in 1911–1913, is a significant Art Nouveau example. The Art Nouveau architecture in the Danube region, including Zagreb, shows two stylistic trends: one using geometric shapes influenced by Viennese models (like Otto Wagner) and another richer in floral ornamentations and motifs from local folk art (like Ödön Lechner).

Romania (Danube Region): The Casa Sofian in Botoşani (1894) blended revival styles with Art Nouveau, notable for its spatial flexibility, asymmetry, light penetration, plasticity, and organic integration with its site and context. In Cincșor, the Lutheran school (1910-1911) used Art Nouveau to express national identity within the Saxon community. The broader Art Nouveau Danube project highlights the prevalence of bourgeois architectural projects (residences, apartment houses, mixed-use urban buildings) in the region, which showcase either floral ornamentations and local folk art motifs or geometric forms influenced by Vienna.

United States:

◦ Louis Comfort Tiffany is celebrated for his Favrile glass and the use of organic and asymmetrical motifs in his designs.

◦ Louis Sullivan in Chicago developed a distinct American variant of Art Nouveau, evident in the stylized floral decoration on buildings such as the Carson, Pirie, Scott and Company Building (1899).

• Netherlands (Nieuwe Kunst): This style is characterized by organic and fluid lines that evoke plant stems and flowers.

Legacy of Organic Forms in Art Nouveau

Despite its relatively brief lifespan, Art Nouveau left an indelible mark on European art and design. It acted as a crucial transitional bridge between Neoclassicism and 20th-century Modernism, fundamentally challenging and breaking down traditional artistic barriers. Its profound emphasis on the unity of the arts (Gesamtkunstwerk) and its innovative use of materials and organic forms continue to resonate in contemporary design. The movement aspired to create a healthier, more natural living environment, even envisioning “Art Nouveau cities” as “artificial forests”. The Secession movement, a worldwide phenomenon, profoundly altered architectural and artistic codes across modern Europe.