Budapest and Vienna are two historically significant cities that played pivotal roles within the Austro-Hungarian Empire, a major European power from 1867 until its dissolution after World War I. As the empire’s capital, Vienna emerged as a central political and cultural hub, while Budapest served as a key center of economic and national identity in the eastern part of the dual monarchy. Both cities are notable for their rich architectural heritage, vibrant cultural landscapes, and the complexities of their political histories, which reflect the diverse ethnic and cultural mosaic of the empire.

During the Austro-Hungarian period, Vienna became synonymous with high culture, particularly in music and the arts, while Budapest nurtured a distinctive identity rooted in folklore and national pride. This cultural dynamism was further fueled by significant economic developments and a modernization drive that transformed both cities into cosmopolitan centers. However, the empire’s efforts to balance the interests of its various ethnic groups often led to tensions and conflicts, as evidenced by political struggles for autonomy that were particularly pronounced in Budapest.

Despite their shared history, Budapest and Vienna exhibited notable differences in their governance and social structures. Vienna operated under a more centralized control, while Budapest experienced significant political instability, which culminated in the challenges faced by its parliament during the empire’s decline. These dynamics not only shaped the identities of the two cities but also set the stage for their post-imperial trajectories, influencing their modern relations and cultural exchanges.

The legacy of the Austro-Hungarian Empire is vividly reflected in both Budapest and Vienna, evident in their architectural grandeur and cultural heritage. From the opulent buildings along Vienna’s Ringstrasse to the iconic Hungarian Parliament Building in Budapest, the remnants of the empire’s ambitious aspirations continue to attract visitors and spark interest in the region’s complex history. Additionally, contemporary efforts to reconcile these historical narratives highlight the ongoing significance of the empire’s dual legacy in shaping the national identities and cultural expressions of both cities today.

Historical Background: The Austro-Hungarian Empire

The Austro-Hungarian Empire, often regarded as one of the most intricate and fascinating political entities of modern European history, was a product of both compromise and necessity. Officially formed in 1867 through the Austro-Hungarian Compromise (Ausgleich), it represented a union between the Austrian Empire and the Kingdom of Hungary, two distinct but closely aligned entities governed by a single monarch—Emperor of Austria and King of Hungary—Franz Joseph I. This dual monarchy was conceived as a strategic response to rising nationalist pressures and the empire’s internal challenges following military defeats, particularly the crushing loss to Prussia in the Austro-Prussian War of 1866. To prevent further disintegration, the Habsburgs, under increasing pressure from Hungarian nationalists, agreed to share power more equitably with the Hungarian elite, leading to a restructured political system that created parallel governments for Austria and Hungary, with shared responsibilities only in foreign affairs, military, and finance.

What made the Austro-Hungarian Empire truly unique was its extraordinary ethnic diversity. It was home to more than a dozen major ethnic groups, including Germans, Hungarians, Czechs, Slovaks, Poles, Ruthenians (Ukrainians), Romanians, Croats, Serbs, Slovenes, and Italians, among others. Each group brought with it distinct languages, traditions, and cultural practices, creating a vast mosaic of identities under one imperial umbrella. This diversity was both a strength and a profound source of internal tension. While it fostered a rich cultural environment, it also meant the central government had to constantly navigate a delicate balance among competing national aspirations, many of which became increasingly assertive in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

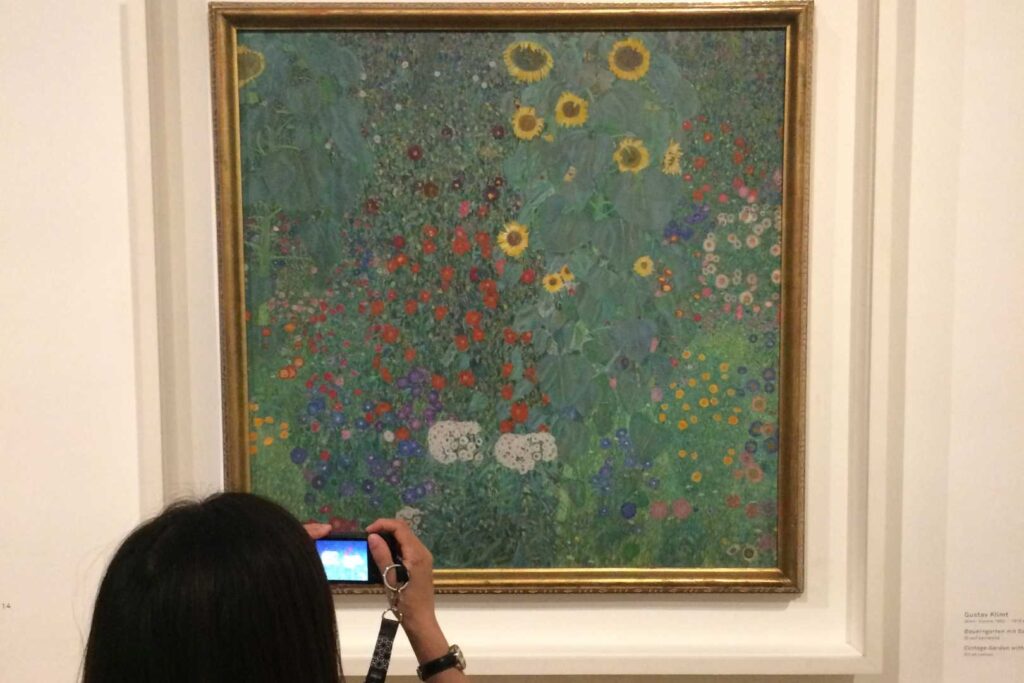

Vienna, the imperial capital, stood at the heart of this polyglot empire, serving not only as a political and administrative center but also as a beacon of European culture and sophistication. The city flourished during the Belle Époque, becoming a vibrant hub for music, visual arts, literature, science, and philosophy. Figures like Gustav Klimt, Egon Schiele, and Otto Wagner were transforming the visual language of modern art and architecture, while Sigmund Freud was revolutionizing the understanding of the human mind. Viennese cafés buzzed with intellectual debate, often blurring the boundaries between disciplines, as artists, scientists, writers, and political thinkers gathered in the spirit of exchange. The city’s architecture reflected its dual impulses: the grandeur of imperial tradition, visible in the Ringstrasse’s stately buildings and palaces, contrasted with the innovative curves and elegance of Art Nouveau, or Jugendstil, which represented a cultural yearning to break from the past and embrace a new aesthetic consciousness.

Budapest, the co-capital of the empire, developed in parallel, asserting its own identity and pride as the center of Hungarian culture and politics. Following the unification of Buda, Pest, and Óbuda in 1873, the city underwent a rapid transformation, becoming a symbol of Hungarian modernity and ambition. Grand avenues, bridges, and public buildings were constructed in an effort to rival Vienna, reflecting both a shared imperial vision and a distinctly Hungarian character. The Chain Bridge, the Hungarian Parliament, and the dramatic views along the Danube embodied a national confidence and a commitment to European sophistication, even as underlying tensions with Austrian political dominance continued to simmer beneath the surface.

The empire was, in many ways, a microcosm of Europe itself—full of contradictions, tensions, and beauty. It was forward-looking yet deeply rooted in tradition; bureaucratically rigid yet artistically daring. Its society was stratified, with an aristocratic elite holding much of the power, but the emergence of a middle class, fueled by industrialization and economic growth, began to challenge the status quo. Railways expanded, factories multiplied, and cities swelled with migrants seeking work and opportunity. The bureaucracy was dense and often slow-moving, but the infrastructure of the empire continued to modernize, especially in transportation and communication, knitting together its vast and varied territories.

Despite its impressive cultural and intellectual vitality, the Austro-Hungarian Empire was riven by unresolved tensions. Nationalist movements grew increasingly vocal and organized, especially among the Slavic populations in the Balkans and the Czechs in Bohemia. The empire’s efforts to assert greater control over Bosnia and Herzegovina, officially annexed in 1908 after decades of de facto administration, further inflamed ethnic tensions and drew the ire of neighboring Serbia and its protector, Russia. These actions, driven in part by the need to maintain imperial prestige and strategic depth in the increasingly volatile Balkan region, exacerbated the already fragile balance of power in Southeastern Europe. The Balkans, often described as the “powder keg of Europe,” became the focal point of imperial rivalries and nationalist agitation.

Russia, positioning itself as the champion of Slavic peoples and protector of Orthodox Christians in the Balkans, viewed Austro-Hungarian expansion as a direct threat to its influence. This created a dangerous geopolitical friction, particularly as alliances were drawn tighter in the years leading up to the First World War. Austria-Hungary aligned itself with Germany through the Triple Alliance, while Russia gravitated toward France and Britain, forming the Triple Entente. These alliances would later crystallize into the opposing sides of World War I, with the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo in 1914—by a Bosnian Serb nationalist—serving as the immediate catalyst for the global conflict that followed.

Yet, for all its political instability and looming crisis, the Austro-Hungarian Empire left behind an extraordinary cultural and architectural legacy. Its cities remain treasure troves of Central European elegance and innovation. From the baroque palaces of Vienna to the Art Nouveau façades of Budapest, from the folk traditions of Transylvania to the literary salons of Prague, the empire produced a unique blend of local and cosmopolitan influences that continue to shape European identity today. The empire’s cultural achievements were not just the result of imperial patronage but also the product of its multiethnic composition—an alchemy of perspectives, styles, and voices that found fertile ground in the shared spaces of cities, schools, and salons.

In literature, music, and visual arts, the empire saw an outpouring of creativity that reflected both the anxieties and aspirations of a world on the brink of modernity. Writers like Franz Kafka, Stefan Zweig, and Joseph Roth captured the paradoxes of imperial life—its grandeur, its melancholy, its sense of impending dissolution. Composers such as Gustav Mahler and Anton Bruckner infused their works with emotional depth and philosophical gravity, while artists associated with the Vienna Secession challenged academic norms and celebrated expressive freedom. The Secession’s motto—“To every age its art, to every art its freedom”—encapsulated the cultural spirit of a society trying to reinvent itself amid the tensions of tradition and transformation.

Ultimately, the Austro-Hungarian Empire was a paradoxical creation—both a last bastion of old-world monarchy and a laboratory of modernism. It was a place where empires met and cultures collided, where innovation thrived amid political stagnation, and where beauty often served as a counterweight to deep social and political divides. Though the empire disintegrated in the aftermath of World War I, its legacy endures—not only in the art, architecture, and literature of Central Europe, but also in the memory of a time when diversity and complexity were woven into the very fabric of governance. Its story remains a poignant reminder of the possibilities and perils of multinational coexistence in an age of competing national identities.

Economic and social changes

The 19th century marked a profound transformation in the economic landscape of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, ushering in an era of modernization that dramatically reshaped its infrastructure, industries, and society. As the feudal order gradually gave way to capitalist modes of production, the empire embarked on an ambitious journey of economic development, driven by necessity as much as by vision. At the heart of this transformation was the gradual dismantling of traditional agrarian hierarchies and the emergence of a market-driven economy, which brought both opportunity and disruption across the empire’s vast and diverse territories.

One of the most pivotal developments in this period was the creation of a unified financial structure to support economic growth and integration across the dual monarchy. The National Austro-Hungarian Bank, established in 1878, became a cornerstone institution, designed to serve both Austria and Hungary while maintaining parity in monetary policy. The bank’s dual headquarters in Vienna and Budapest symbolized the empire’s complex political arrangement and economic interdependence. It played a critical role in stabilizing currency, regulating credit, and encouraging investment across the monarchy’s many regions, linking urban centers with rural markets and supporting the growth of private banking networks.

Industrialization surged, particularly in the empire’s western and northern provinces, including Bohemia, Moravia, and Lower Austria, which rapidly became centers of heavy industry, textiles, and mechanical engineering. Cities like Brno and Prague experienced rapid growth as they developed into industrial hubs that attracted a rising working class and new layers of skilled labor. The expansion of coal mining, steel production, and machine manufacturing in these areas mirrored the broader European industrial trends, and contributed to the modernization of agriculture and transportation elsewhere in the empire. Meanwhile, the eastern and southeastern regions—such as Galicia, Transylvania, and parts of Croatia and Bosnia—remained predominantly agrarian, characterized by large estates, subsistence farming, and slower rates of economic change. These regions supplied much of the food and raw materials for the more industrialized west, reinforcing regional economic disparities that would later have political consequences.

Agricultural reform was another important factor in the empire’s economic evolution. The abolition of serfdom earlier in the century had created a new class of landowners and smallholders, particularly in Hungary, but land distribution remained highly unequal. In some parts of the empire, such as Galicia, peasant poverty was endemic, and rural populations faced chronic underemployment and poor access to credit or education. Nevertheless, improvements in transportation and market access allowed some regions to participate more fully in the imperial economy, and agricultural exports such as grain, livestock, and wine became vital components of imperial trade, particularly to Germany and Italy.

The development of an expansive railway network was one of the empire’s crowning achievements, both a symbol and a catalyst of its economic modernization. By the turn of the 20th century, the Austro-Hungarian Empire had one of the most advanced railway systems in all of Europe, with over 43,000 kilometers of track. Railways linked the farthest corners of the empire to major urban centers, facilitating not only the movement of goods and resources but also people and ideas. The integration of transportation infrastructure also allowed for more efficient military mobilization and administrative control, a crucial consideration in such a geographically sprawling and ethnically fragmented polity. Vienna and Budapest, as twin capitals, became central nodes in this web of connectivity, serving as command centers of commerce, finance, and cultural life.

This period of economic dynamism also brought significant shifts in the empire’s social fabric. As industrialization accelerated, cities grew at unprecedented rates. Urban centers like Vienna, Budapest, Prague, and Lviv attracted migrants from across the empire—Czechs, Slovaks, Croats, Jews, Ruthenians, Germans, and Hungarians—each group bringing with it distinct cultural traditions, languages, and social norms. These cities evolved into dynamic, multicultural spaces, filled with new apartment blocks, factories, department stores, cafés, and theaters. The growth of the middle class—merchants, professionals, civil servants, and entrepreneurs—introduced new patterns of consumption and lifestyle, and also laid the foundations for a more politically conscious and economically influential bourgeoisie.

At the same time, the working class began to organize in response to the difficult conditions of industrial labor, poor housing, and limited legal protections. Socialist movements and labor unions gained traction, particularly in the industrialized regions of Austria and Bohemia. These movements not only advocated for workers’ rights but also added to the growing chorus of political voices demanding reform, national recognition, or greater autonomy. The industrial economy had created new connections between people and places, but it also sharpened inequalities and contributed to the rise of class-consciousness and nationalist fervor, which threatened the coherence of the empire’s fragile balance.

The intersection of economic modernization and cultural development became particularly evident in Vienna and Budapest, where the wealth generated by industry and finance helped fuel a golden age in the arts, architecture, science, and education. Public investment in universities, museums, and concert halls reflected the growing prestige of intellectual and artistic pursuits. New artistic movements like the Vienna Secession embodied the spirit of innovation, challenging traditional academic standards and celebrating modernity, individuality, and the idea of Gesamtkunstwerk—the total work of art. These artistic expressions often paralleled the broader social currents of the time, exploring themes of alienation, identity, and change within the empire’s rapidly evolving social landscape.

In Hungary, economic development went hand-in-hand with a concerted effort to assert national identity through architectural and cultural renewal. The construction of monumental buildings in the Gothic Revival and Neo-Renaissance styles in Budapest was not just an expression of national pride, but also a declaration of cultural parity with Vienna. Hungarian elites promoted the Magyarization of public life, particularly in education and administration, creating further tensions with non-Hungarian populations within the Kingdom of Hungary.

Despite these deepening divides, the empire’s economic transformation created an unprecedented interdependence between its regions, peoples, and institutions. Investment in infrastructure, trade, and human capital had linked disparate provinces into a semi-cohesive economic whole. However, this development did not translate into political unity. As national movements gained momentum and the empire’s leadership struggled to adapt its political system to meet the demands of its increasingly diverse and politically active populations, the contradictions of the dual monarchy became more pronounced.

By the eve of World War I, the Austro-Hungarian Empire stood as a paradox: a state of immense economic and cultural vitality, yet one strained by the competing forces of modernity and tradition, unity and fragmentation. Its railways connected provinces more efficiently than ever before, its banks facilitated cross-border investment, and its cities sparkled with cosmopolitan ambition. Yet beneath this surface of prosperity lay the unaddressed grievances of marginalized communities, the instability of a dual system under constant negotiation, and the growing challenge of nationalism, which ultimately proved more powerful than the empire’s economic glue. What had once been a dynamic experiment in imperial adaptation became increasingly brittle, as economic success could not overcome the mounting political pressures that would soon engulf Europe in the First World War.

Political dynamics

The internal politics of the Austro-Hungarian Empire were shaped by a web of contradictions, compromises, and competing ambitions that defined its very existence from the moment of its creation in 1867. The empire’s dual structure—uniting Austria and Hungary under a single monarch but with separate governments and parliaments—was an uneasy solution to the demands of Hungarian nationalists for autonomy. Yet it left other national groups—Czechs, Slovaks, Romanians, Croats, Serbs, Ukrainians, Poles, Italians—without comparable recognition, despite their significant demographic weight and deep-rooted cultural identities. The result was a state in which power-sharing became a perpetual balancing act and where any political movement by one group inevitably triggered reactions from others. The monarchy was constantly engaged in a delicate dance to hold the diverse components of the empire together without granting any one faction enough leverage to destabilize the whole.

Efforts at political reform were numerous but largely ineffectual in resolving the underlying ethnic tensions. Perhaps the most radical and visionary proposal came from Aurel Popovici, a Romanian intellectual and political thinker, who in 1906 introduced the idea of “United States of Greater Austria.” His plan envisioned the transformation of the empire into a federation of 15 semi-autonomous ethnically defined states. These units would reflect the cultural and linguistic makeup of the empire, theoretically granting each group a voice in governance. However, as idealistic and forward-thinking as Popovici’s plan was, it ran headlong into the complexities of geography and demography. Many regions were so ethnically mixed that drawing clean borders was nearly impossible. Furthermore, the Austrian and Hungarian elites saw the federal model as a threat to their own privileged positions and refused to entertain any dilution of their authority.

Compounding the political tension was the rigid structure of the imperial government, where real power remained concentrated in the hands of a small German-speaking Austrian aristocracy and, to a lesser extent, the Hungarian nobility. In Hungary, policies of Magyarization attempted to assimilate non-Hungarian groups through education, language laws, and public administration—provoking fierce resentment among Slovaks, Romanians, Croats, and others. In the Austrian half of the empire, while the German language held primacy in official settings, some concessions were made to Slavic groups, particularly the Czechs in Bohemia and the Poles in Galicia. Still, these gestures rarely satisfied demands for true autonomy or cultural equality.

Despite the political gridlock and rising ethnic tensions, the dual capitals of Vienna and Budapest thrived as cosmopolitan centers of intellectual and artistic life. Vienna, the imperial seat, dazzled with its grand boulevards, stately palaces, and vibrant café culture. It was a hub for avant-garde art and music, producing figures like Gustav Mahler, Arnold Schoenberg, and Otto Wagner. At the same time, it was a crucible of revolutionary thought and philosophical inquiry, where thinkers like Sigmund Freud, Karl Kraus, and Ludwig Wittgenstein explored the psyche, language, and modernity itself. The city’s contradictions—luxurious and anxious, conservative and radical—mirrored the empire’s own identity crisis.

Budapest, on the other hand, emerged as a symbol of Hungary’s rising national consciousness and modernization. Following the Compromise of 1867, massive investments transformed the city into a modern European capital, complete with grand avenues, neoclassical public buildings, and a metro system—one of the first on the continent. The Parliament building on the Danube, inspired by Westminster, was a bold declaration of Hungarian ambition and identity. Hungarian literature, music, and political life flourished, and Budapest became a dynamic urban center whose energy contrasted with Vienna’s imperial decorum. Still, beneath the surface, the tensions of identity played out in the streets, in the press, and in public discourse, as non-Magyar communities struggled against cultural homogenization.

Throughout the final decades of the empire, every attempt at reform was constrained by the zero-sum nature of its internal politics. A concession to one group was viewed as a betrayal by another. The Habsburg monarchy, aging and increasingly out of step with the needs of a modern society, tried to project an image of unity while relying more and more on the tools of censorship, bureaucracy, and military presence to maintain order. Emperor Franz Joseph, who reigned for nearly seven decades, was a stabilizing symbol for many, but his death in 1916 left a vacuum of authority at the very moment the empire faced its greatest existential threat.

As Europe edged toward war, the internal contradictions of the Austro-Hungarian Empire became more apparent and dangerous. Nationalist agitation intensified, particularly in the Balkans, where Serbian-backed movements clashed with Habsburg authority. The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo in 1914 was not just a trigger for global conflict—it was the ultimate consequence of the empire’s unresolved national tensions and its inability to reform itself from within. The empire’s multi-ethnic composition, once its strength and source of rich cultural vitality, became an Achilles’ heel when national identities grew stronger than imperial loyalties.

World War I pushed the fragile structures of Austro-Hungarian politics to the breaking point. The prolonged war effort drained resources, eroded civilian morale, and exposed deep-seated divisions. Ethnic regiments within the imperial army began to desert or turn against the monarchy, while nationalist leaders in exile lobbied the Allies for the recognition of independent nation-states. The Czech, Slovak, South Slavic, and Romanian leaders increasingly viewed the war as an opportunity for liberation rather than imperial preservation. By the end of the war in 1918, internal revolt and external defeat had completely dismantled the empire.

What remained was a scattering of new nations—Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia, Austria, Hungary, parts of Poland, Romania, and Italy—each carrying fragments of the old imperial mosaic but bound now by national boundaries and ideologies. The fall of the Austro-Hungarian Empire was not just the collapse of a political entity, but the end of a particular vision of multi-ethnic coexistence under a supranational structure. Its failure reflected not a lack of cultural richness or intellectual innovation, but the inability of its political framework to accommodate the profound diversity that was its most defining characteristic. The ghost of the empire lingers in Central Europe’s architecture, languages, cuisines, and memories—a legacy both celebrated and mourned.

Budapest

Budapest’s architectural tapestry weaves together centuries of history, culture, and identity, making the city one of Europe’s most visually engaging urban landscapes. From medieval remnants to modernist curves, the city’s structure tells the story of shifting empires, revolutions, and artistic revolutions. Each neighborhood reveals another layer of this chronicle. Walking its streets is like stepping through a timeline—Baroque facades melt into Neoclassical grandeur, which in turn gives way to the flamboyance of Neo-Gothic, the grace of Art Nouveau, and the functionalism of modern design. This vast stylistic diversity has earned Budapest not only architectural acclaim but a significant place in global cinema, where it often stands in as a visual double for cities like Paris, Vienna, Berlin, or Buenos Aires. Directors are drawn to the city’s ability to echo multiple eras, from imperial splendor to postwar minimalism, often within a single city block.

The Parliament Building stands as one of the most commanding architectural feats in Europe, and certainly one of Hungary’s greatest symbols of nationhood. Completed in 1904, it stretches along the Danube with majestic precision, blending the vertical thrust of Neo-Gothic design with baroque ornamentation and Renaissance symmetry. Its vast size, detailed statuary, spires, and decorative turrets mirror the ambition and grandeur of the Austro-Hungarian Empire at its height. Inside, vaulted ceilings, golden staircases, and stained-glass windows create a ceremonial space that is both nationalistic and universally awe-inspiring. It serves not just as the seat of government but as an enduring expression of identity, resilience, and artistic commitment.

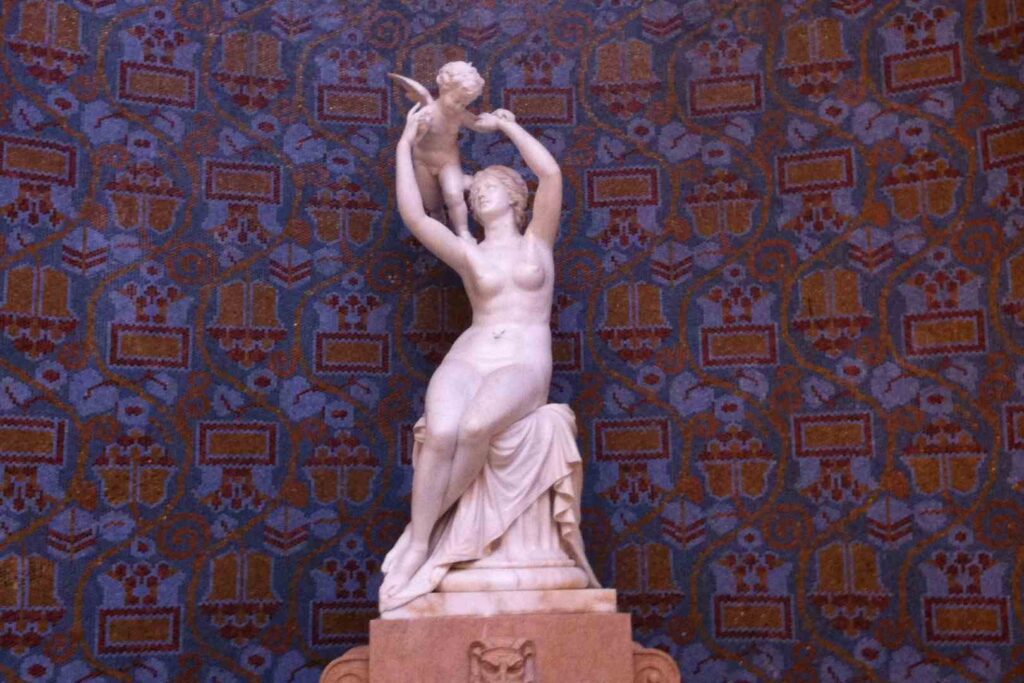

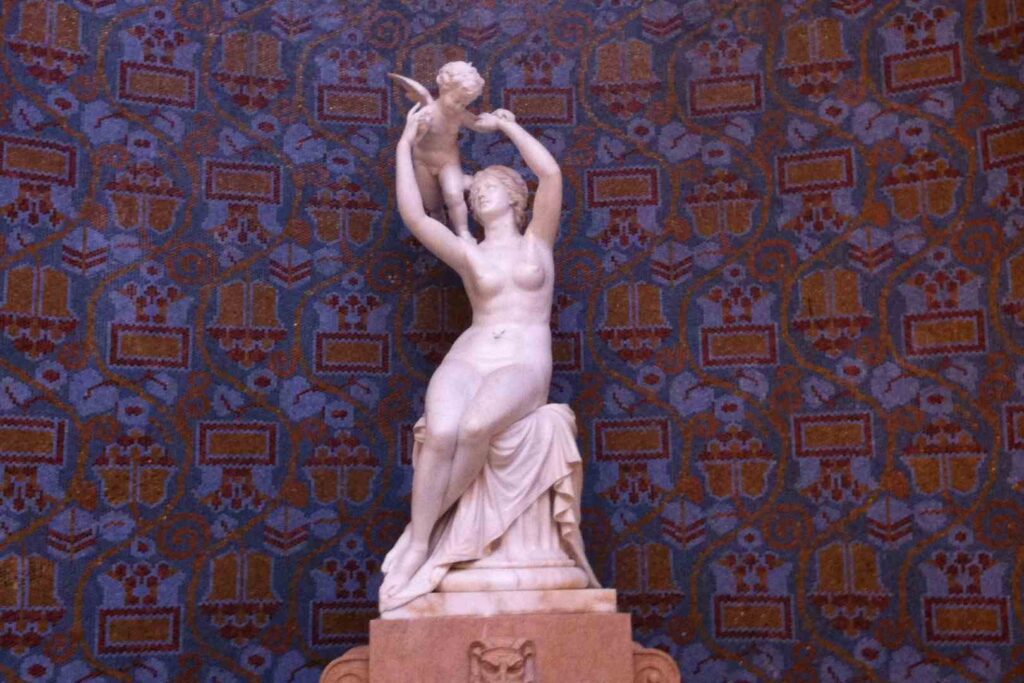

Alongside political monuments, Budapest developed into a sanctuary for the performing arts, and few places illustrate this more richly than the Hungarian State Opera House. Designed by Miklós Ybl, one of Hungary’s most celebrated architects, the Opera House opened in 1884 as a jewel of Neo-Renaissance elegance. With its frescoed ceilings, sweeping staircases, and gilded balconies, it was a place where the city’s growing middle class could gather, celebrating culture in opulent surroundings once reserved for aristocracy. The attention to detail within its interiors speaks to the period’s broader values—an era where aesthetics, nationalism, and refinement were seen as deeply interconnected.

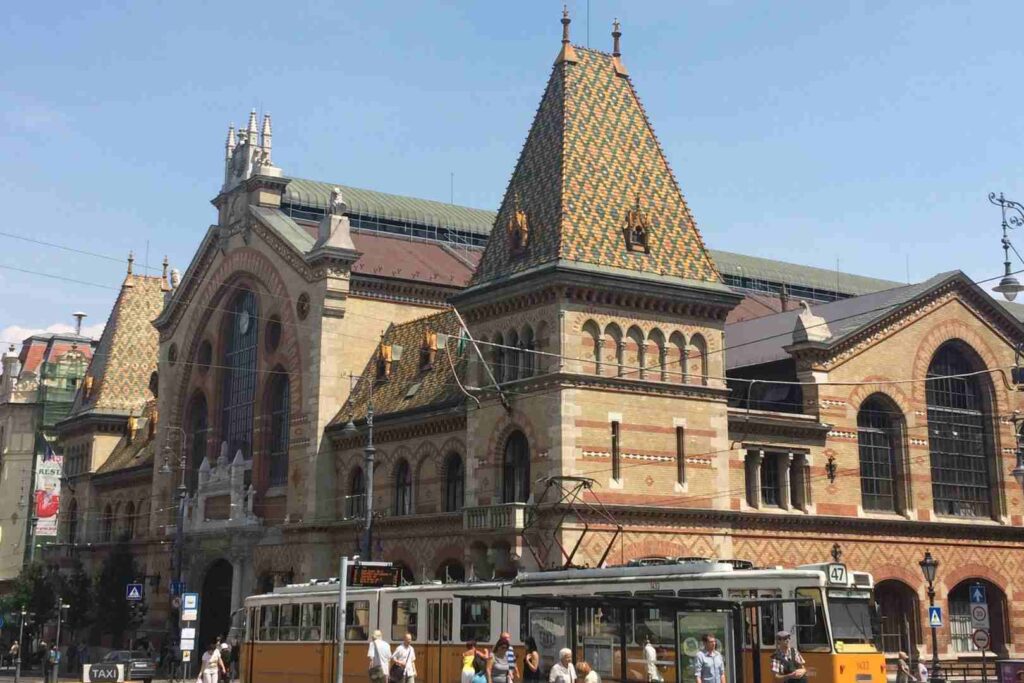

As Budapest surged into the 20th century, Art Nouveau—known in Hungary as “Szecesszió”—offered a bold new architectural language, a defiant break from historicism, and a celebration of the unique. Where earlier buildings borrowed heavily from classical models, the Art Nouveau movement in Hungary sought inspiration from its own soil: Hungarian folk tales, floral motifs, and traditions of craftsmanship. This movement brought with it an organic quality to the city’s skyline. Wrought iron balconies curled like vines, facades blossomed with ceramic flowers, and interior spaces came alive with color and asymmetry. The Gresham Palace, constructed at the turn of the century as an office building and now repurposed as a luxurious hotel, is perhaps the crown jewel of this style. Its stained glass, detailed mosaics, curved glass canopies, and stylized floral flourishes encapsulate both the elegance and the energy of this artistic explosion.

This wasn’t just an aesthetic trend; it reflected a broader cultural ambition. Hungarian artists and intellectuals were seeking to assert their national identity within the diverse and often German-dominated Austro-Hungarian Empire. Art Nouveau gave them a creative outlet through which they could express something distinctly Hungarian—colorful, rooted in tradition, yet boldly forward-looking. Buildings like the Museum of Applied Arts or the Postal Savings Bank shimmer with Zsolnay ceramic tiles, playful facades, and interior spaces designed to evoke both past myths and future ideals. Each Art Nouveau structure in Budapest is a fusion of architecture, art, and storytelling.

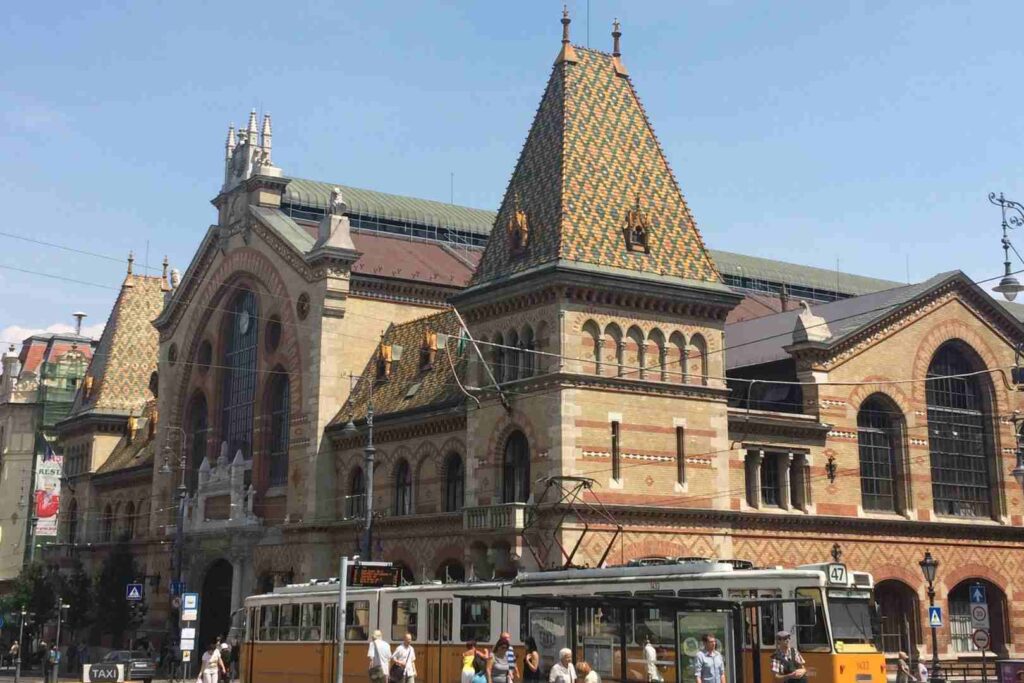

Behind the architectural splendor lies a more complex and often turbulent history. The unification of Pest, Buda, and Óbuda in 1873 was more than a logistical development; it was a symbolic assertion of Hungary’s role within the dual monarchy. This newly unified capital became a canvas upon which civic pride, modern industry, and imperial rivalry were projected. Massive infrastructure projects reshaped the urban landscape: bridges connected the sides of the Danube, new boulevards were laid down, and ornate public buildings arose to house the institutions of a modernizing society. Yet this golden age was also laced with anxiety. The city grew rapidly, absorbing waves of migration from the countryside and further afield. Budapest became a meeting point of cultures, languages, and classes—dynamic, vibrant, but also volatile.

The 20th century left deep marks. The visual record of Budapest’s resilience and struggle is etched into its buildings—scarred by bullet holes from the Second World War and the 1956 Revolution. The grandeur of the past stands cheek-by-jowl with reminders of oppression, defiance, and survival. This juxtaposition is not sanitized or hidden; it is part of what gives the city its raw authenticity. Restorations coexist with ruins. Austere postwar apartment blocks loom over baroque palaces. Soviet-era mosaics fade beside Neo-Gothic chapels. The result is a city that doesn’t erase its history but carries it openly.

Today, Budapest continues to build on its layered architectural legacy. Contemporary design studios and restoration experts work side by side to preserve the city’s heritage while pushing its aesthetic boundaries forward. Cultural institutions continue to find new life within historic buildings—concert halls in old market halls, galleries in former palaces, boutique hotels in grand mansions. There’s a palpable sense that the city is still evolving, still telling its story through bricks, glass, and steel.

Budapest’s beauty isn’t static—it moves. It changes with the light, with the seasons, with each generation that adds its voice to the city’s chorus. Whether wandering through the leafy avenues of Andrássy út, marveling at the whimsical facades of the Jewish Quarter, or taking in the skyline from the Fisherman’s Bastion, visitors find not just architectural excellence but a profound sense of place—deep, textured, resilient. It is a city whose walls speak in multiple tongues, whose skyline bears witness to both empire and revolution, and whose creativity continues to flow through every archway and iron gate.

Vienna

Vienna, as the capital and intellectual heart of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, stood not only as the seat of imperial power but also as a radiant epicenter of cultural and political life. Its evolution from a Roman frontier post known as Vindobona into one of the great capitals of 19th-century Europe tells a story of layered identities, imperial ambition, and artistic brilliance. The city’s location along the Danube provided natural connectivity to the rest of Europe, allowing trade, diplomacy, and ideas to flow through its streets, and shaping it into a truly cosmopolitan hub by the late 1800s.

During the height of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Vienna exemplified the grandeur of imperial aspirations. The city was transformed through monumental architecture and urban planning designed to reflect the might, diversity, and elegance of the empire. The Ringstraße, constructed in the mid-19th century on the site of the old city walls, became a showcase of architectural innovation and eclecticism. Here, monumental buildings rose—parliament houses, museums, palaces, and opera houses—built in a blend of historicist styles: Neo-Renaissance, Neo-Gothic, Neo-Baroque. These styles weren’t merely aesthetic choices, but symbolic ones, aiming to evoke continuity with great civilizations of the past while legitimizing the modern imperial project.

Architects such as Theophil Hansen and Otto Wagner played key roles in shaping the face of the city. Wagner, in particular, emerged as a visionary who helped usher Vienna into the modern age. His buildings, including the Austrian Postal Savings Bank, incorporated Art Nouveau elements with a stark, rational functionality, embodying the era’s tension between ornament and utility. The Secession Building, adorned with the motto “To every age its art, to every art its freedom,” became the visual manifesto of a generation of artists who wanted to break free from academic tradition and explore the psychological, the symbolic, and the spiritual in new ways.

This was not simply a stylistic rebellion, but part of a broader cultural awakening. The city was alive with ferment in every discipline. Composers such as Gustav Mahler and Arnold Schoenberg were pushing music beyond its tonal boundaries, while Sigmund Freud, working just a short distance away, was exploring the hidden dimensions of the human psyche. Coffeehouses buzzed with debate and discussion, serving as informal academies for poets, politicians, and philosophers. The Viennese fin-de-siècle was as much about anxiety and introspection as it was about opulence and optimism, a tension that echoed the fragility of the empire itself.

Ethnographic shows, though less remembered today, were a major feature of Vienna’s public culture during this era. These exhibitions, often staged in venues like the enormous Rotunda built for the 1873 World’s Fair, presented curated spectacles of the empire’s many ethnic groups. Visitors could witness staged performances of music, dance, and craft from peoples across the Habsburg lands—from Ruthenians to Bosniaks, from Czechs to Croats. On one hand, these spectacles highlighted the vast cultural diversity of the empire and attempted to foster a sense of imperial unity. On the other, they exoticized and reduced complex cultures into digestible entertainment, often reinforcing stereotypes and echoing colonial modes of representation. They revealed the contradiction at the heart of the empire’s multiculturalism: an uneasy balance between inclusion and hierarchy, between pride in diversity and the desire for control.

Politically, Vienna held the delicate reins of governance over a fragmented, multilingual realm. The imperial court, housed in the sprawling Hofburg Palace, symbolized both authority and the challenges of rule. From Vienna, the Emperor attempted to hold together an empire made up of Czechs, Slovaks, Hungarians, Poles, Slovenes, Croats, Serbs, Italians, Ukrainians, Jews, and Germans—all with competing national identities and ambitions. Reforms were often slow and contested. Autonomy movements gained strength in the regions, while bureaucrats in Vienna struggled to craft policies that would not alienate vital constituencies. The empire’s dualist structure—created in 1867 to appease Hungary—provided some balance but left other groups feeling marginalized, feeding the rise of nationalism that would ultimately threaten the empire’s cohesion.

Vienna’s experience during World War I exposed the limits of imperial unity. As resources dwindled and hunger spread, the population of the capital experienced hardship and uncertainty, giving rise to what has been described as a “community of suffering.” The war stripped away much of the city’s outward grandeur, revealing internal fractures and sharpening calls for national self-determination. The once-elegant salons and theaters dimmed under the weight of war, and the streets of the imperial capital bore witness to protests, shortages, and eventually, the collapse of the centuries-old monarchy.

The city’s role within the empire becomes clearer when contrasted with Budapest, its imperial sibling. While both cities were deeply interwoven through economic and cultural ties—particularly after the formation of the customs union in 1850—their political trajectories diverged. Budapest increasingly became the voice of Hungarian autonomy and ambition, a city of assertiveness and reform. Vienna, by contrast, maintained a more centralized and ceremonial authority, often associated with imperial conservatism and bureaucratic inertia. Budapest’s Parliament was a beacon of national pride and political dynamism; Vienna’s was a symbol of pan-imperial order. The tension between these two poles reflected the broader push-pull within the empire—between unity and division, between tradition and transformation.

Economically, Vienna benefited from its position as both a political capital and a center of industrial design and manufacturing. It was at the forefront of the empire’s engagement with modern industry, transportation, and communications, even as it depended heavily on agricultural imports and raw materials from Hungary and beyond. The economic interdependence of the empire’s regions fostered both cooperation and inequality, with Vienna often seen as the beneficiary of imperial privilege.

Yet despite all the contradictions, Vienna remains a city defined by this layered legacy. Its streets and buildings are living archives of a vanished empire—a place where the splendor of Habsburg architecture meets the quiet melancholy of post-imperial memory. It is a city of grandeur and ghosts, where beauty often coexists with loss, and where the past never quite recedes. Today, Vienna continues to thrive as a cultural capital, its museums and concert halls still resonant with the genius of its golden age, and its public spaces still shaped by the ambitions of emperors and the visions of artists who dared to reimagine the world.

Comparision between Budapest and Vienna

The historical relationship between Budapest and Vienna offers a compelling lens through which to examine the multifaceted legacy of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. These two capitals, once pillars of a unified but complex imperial structure, continue to reflect both the commonalities and the contrasts that shaped their trajectories—economically, culturally, architecturally, and politically.

Economically, the ties between Vienna and Budapest were forged through both necessity and design. The Austro-Hungarian customs union, established in 1850, laid the groundwork for extensive interdependence. Vienna, already an established industrial and financial center, benefited from Hungary’s vast agricultural resources, which became crucial to feeding the empire’s growing population and army. Budapest, in turn, grew rapidly as a result of this integration. While it remained primarily agrarian in its surrounding regions, the city itself underwent significant industrialization in the late 19th century. Yet economic disparities persisted: Vienna was often at the forefront of technological and industrial innovation, becoming a key hub for manufacturing, design, and engineering, while Hungary struggled to match this pace outside its urban centers. This asymmetry shaped not only economic policies within the empire but also fed nationalist discontent, especially as Hungarians sought greater economic self-determination.

The cultural landscape of both cities during the imperial period reveals striking differences shaped by both geography and ideology. Vienna’s cultural dominance was characterized by its embrace of classical music, fine arts, and intellectual thought. As the seat of the Habsburg court, Vienna fostered an atmosphere of refinement and elitism that attracted composers like Brahms and Mahler, writers such as Arthur Schnitzler and Stefan Zweig, and revolutionary thinkers including Sigmund Freud. The Viennese fin-de-siècle was marked by a spirit of innovation intertwined with a deep sense of impending change, as seen in the rise of Secessionist art and the psychological introspection of modernist literature.

In contrast, Budapest’s cultural awakening was rooted more strongly in national identity. The Hungarian capital embraced its folk traditions and sought to elevate local customs, languages, and artistic expressions within a broader European context. While Vienna looked outward, aligning itself with pan-European trends, Budapest looked inward, nurturing a sense of cultural uniqueness. Institutions like the Gödöllő Artist Colony promoted a distinctly Hungarian Art Nouveau style (Szecesszió), incorporating folk motifs and traditional craftsmanship into their works. The arts in Budapest were not merely aesthetic pursuits but also political ones, serving as tools for cultural assertion within a dual monarchy often dominated by German-speaking elites.

Architecturally, both cities bear the grandeur of empire, though expressed in different idioms. Vienna’s architectural pride is best captured along the Ringstrasse, a circular boulevard built to symbolize the empire’s might and modernity. Here, buildings such as the Vienna State Opera, the Museum of Fine Arts, and the Parliament exude neoclassical and neo-Gothic grandeur, designed to rival the great capitals of Europe. The emphasis was on balance, symmetry, and the projection of imperial authority. Budapest responded with its own monumental statement—the Hungarian Parliament Building—completed in 1904. With its Gothic Revival style, it not only rivaled its Viennese counterpart in scale and beauty but served as a national symbol, asserting Hungary’s equal stake in the empire. Other architectural highlights in Budapest, including the Fisherman’s Bastion, St. Stephen’s Basilica, and the Great Market Hall, underscore a similar blend of nationalism and imperial splendor, reflecting a dual identity that continues to define the cityscape.

Politically, the two cities navigated the complexities of dual rule in ways that often put them at odds. Vienna represented the centralized power of the Habsburg dynasty and the administrative core of the empire, whereas Budapest was the focal point of Hungarian autonomy. The 1867 Compromise that created the dual monarchy granted Hungary internal self-governance but kept foreign affairs and military policy in Vienna’s hands. This delicate balance bred tensions that were never fully resolved. While Budapest increasingly asserted its legislative independence—sometimes to the frustration of Vienna—the capital of Austria continued to function as the empire’s command center, often resisting calls for further federalization. These political frictions became more pronounced in the early 20th century, as nationalist movements gained momentum across the empire. The dissolution of Parliament in Budapest in 1903 and the resulting years of non-parliamentary rule underscored how fragile the political equilibrium had become.

Despite these tensions, the legacy of the Austro-Hungarian Empire remains vividly alive in both cities. The architectural splendor, the multilingual place names, the cuisines that blend Central European and regional flavors, and the shared cultural institutions all speak to a time when Budapest and Vienna were two faces of a single, albeit complex, imperial identity. Viennese waltzes and Hungarian folk dances, schnitzel and goulash, Secessionist salons and artisan guilds—each tells part of the story of an empire that sought unity through diversity but ultimately collapsed under the weight of its internal contradictions.

In modern times, the relationship between Budapest and Vienna has shifted from imperial hierarchy to cross-border cooperation. Both cities are now capital centers of independent nations, yet they continue to build on their shared heritage through tourism, trade, and cultural exchange. Their twinned histories serve as a foundation for contemporary collaboration, whether in European Union initiatives, academic partnerships, or cultural events celebrating the Danube region’s unity.

Yet they also continue to diverge in meaningful ways. Vienna is often seen as a bastion of liberal politics and progressive governance, regularly topping global rankings for quality of life and urban innovation. Budapest, on the other hand, has taken a more nationalist turn in recent years, with its leadership emphasizing traditional values and historical grievances, particularly those tied to the Treaty of Trianon and the loss of Hungary’s historic territories after the empire’s collapse. These differences echo the unresolved legacies of a shared past and highlight the continuing relevance of imperial history in shaping modern identity and politics.

Ultimately, Budapest and Vienna remain cities of mirrors—reflecting each other’s glories and struggles, their similarities born of a common empire, and their differences shaped by centuries of evolving identity. Together, they embody the richness, complexity, and contradictions of the Austro-Hungarian legacy, offering a living museum of Central European history and a vibrant vision for its future.

Discover Vienna and Budapest with a private guide

Budapest and Vienna, two of Europe’s most elegant and historically rich capitals, offer an unparalleled journey through time, culture, and architecture. While both cities proudly carry the legacy of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, they each maintain a unique atmosphere—Budapest, with its vibrant energy and romantic Danube views, and Vienna, with its imperial refinement and artistic soul. Exploring them is more than just visiting landmarks; it’s about understanding their essence, and the best way to do that is through private, curated tours and local experiences that reveal the cities’ hidden stories and finest details.

Wandering aimlessly through Budapest’s grand boulevards or Vienna’s polished streets can certainly be beautiful—but it often means missing out on the depth and nuance that make these places extraordinary. A private tour lets you go beyond the surface. Whether you’re navigating the labyrinthine courtyards of Buda Castle or admiring the Secessionist façades in Vienna, a tailored experience ensures that what you see is contextualized, alive, and meaningful. You hear the stories behind the buildings, understand the interplay between politics and design, and get access to places most tourists overlook.

For those drawn to art, architecture, and local heritage, the immersive tours available through Art Nouveau Club in Vienna and Art Nouveau Club in Budapest are exceptional. These experiences are not your average city walks—they are thoughtfully crafted journeys through history, culture, and design. You’ll explore the artistic revolutions that shaped each city’s identity, from the elegance of Vienna’s Ringstrasse to the vibrant Hungarian Secessionist gems scattered across Budapest.

In Vienna, the tours dive into the world of Otto Wagner, Koloman Moser, and the Secession movement—where radical thinkers challenged tradition and redefined what modern could mean. You’ll visit buildings that aren’t just beautiful but bold, and understand how they responded to the empire’s cultural transformation.

Meanwhile, Budapest offers its own stunning version of Art Nouveau, infused with local folk elements and symbolism. Through the expert guidance of local hosts, you’ll discover how Budapest used architecture to craft a national identity, from the stylized curves of the Gresham Palace to hidden mosaics and lesser-known artisan masterpieces that tell stories of resilience, pride, and creativity.

What makes these tours special isn’t just the access—they’re personal, passionate, and deeply informed. Guides share not only their expertise but also their perspective, offering recommendations for where to eat, where to relax, and how to feel the city as the locals do.

For anyone seeking to connect with the heart of Budapest and Vienna, private tours are not a luxury—they’re the key. They allow you to move at your own pace, focus on what fascinates you most, and gain a far richer understanding of each city’s past and present. The Art Nouveau Club in both cities offers exactly that: an invitation into the soul of two capitals shaped by art, empire, and ambition.